Universities in some regions of Ontario are under increasing financial pressure as enrolments of high school students decline in those areas. Meanwhile, the provincial government has begun to review the formula it uses to allocate funding to the province’s 20 universities, adding further uncertainty to the situation.

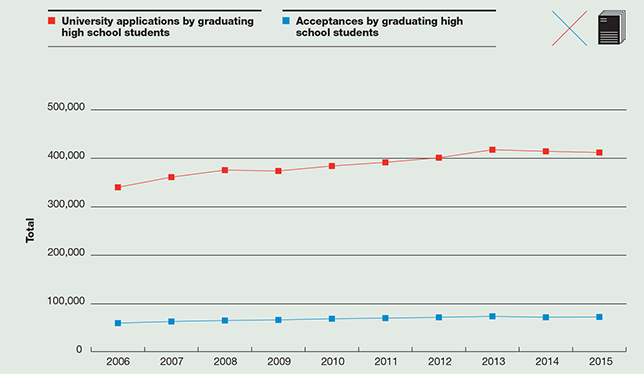

University applications submitted by high school students declined in 2015 for the second consecutive year, to 412,096, down 0.6 percent from 2014 and down 1.4 percent from the previous year, according to the Ontario Universities’ Application Centre. The drop reflects a decline in the number of university-aged students in the province, a trend that is expected to continue for several more years.

While acceptances by students in this age group rose slightly to 71,624, there was a wide discrepancy among institutions. Schools in Toronto and its surrounding areas generally saw steady growth while universities in less populous regions were down. Confirmations declined by 17.2 percent at Algoma University in Sault Ste. Marie, 16.5 percent at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, 14.3 percent at Laurentian University in Sudbury, and 8.9 percent at the University of Windsor.

Overall enrolment levels are expected to remain flat over the next five years, posing challenges for some institutions, said Chris Monahan, director of research and planning at the Ontario Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities. By 2020, enrolments are expected to grow, along with the youth population, but the rebound probably won’t mirror the robust growth that institutions saw over the past decade, said Mr. Monahan. He made the remarks at a symposium hosted by the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto in May.

Full-time undergraduate enrolment in Ontario universities surged by more than 40 percent over the past 10 years, a larger increase than that seen in the 1960s, driven largely by growing participation rates, he noted.

Nor is the projected growth after 2020 expected to be equal across the province. “For some institutions this is a permanent crisis,” said Alex Usher, president of Higher Education Strategy Associates, a Toronto-based consulting firm. These schools could face “significant” financial difficulties, he said, since about half of university operating revenues come from tuition fees, which depend completely on enrolment levels.

Still, some universities have managed to buck the trend. Nipissing University in North Bay reported an 8.3-percent increase in acceptances this year, thanks to its strong recruitment efforts in the Toronto area. The University of Ottawa, which saw just a 0.6-percent dip in confirmations, has capitalized on its bilingual status to appeal to students in Quebec, Mr. Usher noted.

For some universities, the answer was to accept more international and graduate students, offsetting what would have been an even more pronounced downturn. At the University of Windsor, international students’ academic fees comprise about one-third of the institution’s total tuition revenue, up from 15 percent five years ago, noted its president, Alan Wildeman, saying the change has contributed to the university’s stable finances.

U of Windsor is looking to its U.S. neighbours to help maintain the trend. Last year it introduced discounted international tuition fees of about $10,000 for U.S. students, similar to what public universities in nearby Michigan charge domestic students. U of Windsor plans to intensify its student recruitment efforts in neighbouring regions in the U.S., Dr. Wildeman said. Despite falling enrolment, the university has pledged to hire up to 50 full-time faculty members in addition to those who are being hired to replace retiring professors; it will finance that by tapping a $45-million strategic priority fund. “It’s part of our strategy to really differentiate the University of Windsor as a place that continues to emphasize the student experience,” Dr. Wildeman said.

Change in popular programs

Shifting enrolment patterns have also affected how the student body is distributed across campus, he said. U of Windsor, like many other universities, has seen enrolments in business, engineering, law and other professional degrees increase while demand for the arts, humanities and social sciences has shrunk from almost 50 percent of overall enrolment to about one-third. The school plans to move to a flexible budgeting system that will allow it to allocate resources to growing areas without compromising other faculties, said Dr. Wildeman, acknowledging that this change “will not be easy.”

Enrolment pressures are hurting not only tuition revenues but also affecting operating grants that institutions receive from the Ontario government. Laurentian University said in a news release that the 2015-16 academic year will mark the ninth consecutive year that its per-student provincial funding has declined, and for the first time, provincial grants will constitute less than half of the university’s overall revenues.

In March, Ontario launched a review of the formula it uses to divvy up the $3.5 billion a year it gives universities. Almost 80 percent is allocated to individual institutions based on historic enrolment levels. Although the purpose of the review isn’t to deal with effects of declining enrolment, it is happening at a time when the government “is genuinely worried about the finances of a few institutions,” said Mr. Usher. “And those worries do stem from enrolment problems.”

Harvey Weingarten, president and chief executive of the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario, or HEQCO, said that in an era of declining enrolment, the current funding model is “a disaster” for some institutions. Universities have generally relied on robust enrolment growth to cover rising expenses over the past decade and some will no longer be able to do so. HEQCO has urged the government to amend its funding formula to make it more dependent on outcomes other than enrolment levels, leaving it to the government to determine what those outcomes should be.

Others are urging caution. In an opinion piece published in the Ottawa Citizen, Carleton University President Roseann O’Reilly Runte warned that changes to funding formulas in other countries have caused instability and placed already fragile institutions “at great risk.”

Enrolment pressures are even more pronounced in Atlantic Canada. The Nova Scotia government recently passed controversial legislation allowing universities that face “serious financial trouble” to restructure, a process that could suspend the right to strike at those institutions and make it easier for to reduce staff.

Governments across Canada have shown that they aren’t willing to keep increasing funding to postsecondary institutions at the same pace as they have in the past, said Dr. Weingarten, adding that enrolment growth “is not going to solve this problem.”