It was late September when Jacques Brodeur heard from freelance photographer Anand Varma that one of the photos he’d taken in Dr. Brodeur’s lab was going to be on the cover of National Geographic magazine’s November issue. “But there was an embargo on the photo and it wasn’t until the end of October when I got a copy of the magazine that I could finally see it. It was magnificent! And the lighting! I was flabbergasted.” Dr. Brodeur, an entomologist and professor in the biological sciences department at Université de Montréal, says it was a proud moment for him: he grew up reading National Geographic since his parents had a subscription.

Mr. Varma had travelled to Dr. Brodeur’s lab at the Institut de recherche en biologie végétale in July 2013 to take photos for a story in National Geographic entitled “Mindsuckers.” The article describes how unsuspecting ladybugs become hosts to a parasitic little wasp called Dinocampus coccinellae, a process that Dr. Brodeur and his research team have been documenting for the past five years.

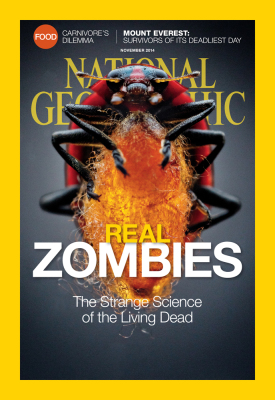

When a female wasp stings a ladybug, it lays a single egg inside which begins to grow. When ready, the wasp larva emerges through the ladybug and spins a cocoon between the bug’s legs – the stage of the process that was caught so spectacularly in the National Geographic photo. Though its body is now free of the tormentor, the ladybug “remains enslaved, standing over the cocoon and protecting it from potential predators,” according to the article.

Student Fanny Maure and her colleagues in Dr. Brodeur’s lab may have discovered how this process works. They found that when the wasp injects its egg into the ladybug victim, it also injects a virus that replicates in the wasp’s ovaries. They suspect that it’s the virus that immobilizes the ladybug, turning it into a kind of zombie bodyguard. Amazingly, many ladybugs survive the ordeal.

Taking a photo of the process, however, was no easy task. Mr. Varma arrived at the lab “with tons and tons of equipment,” says Dr. Brodeur, and clicked away over the course of five days. “I took 2,249 images of ladybugs infected with wasp larvae,” says Mr. Varma, “and the magazine chose the very last frame to put on the cover.”