Valerie Walker admits it wasn’t so long ago that she was “that grad student” wondering what the heck she was going to do if she didn’t stay in academia. After graduating in 2009 with a PhD in physiology from McGill University, she said she was “open to options.” She just didn’t know what those options were.

“I really enjoyed research and teaching and communicating knowledge, whether to undergrads in a class or to other academics at conferences,” recalled Dr. Walker, who now serves as director of policy at the not-for-profit organization Mitacs. “I wouldn’t have thought when I was doing my PhD, ‘Oh, I’m going to be a director of policy.’ What is that?”

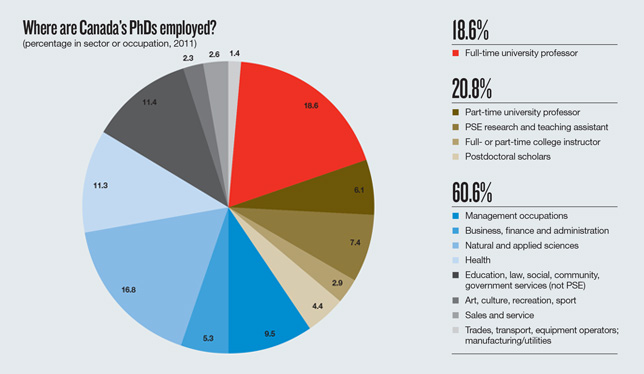

Most PhD graduates set their sights on academia – and nearly 40 percent do work in the postsecondary education sector, according to a recent report by the Conference Board of Canada, Inside and Outside the Academy: Valuing and Preparing PhDs for Careers. However, the report noted that less than one in five PhDs – 18.6 percent – end up employed as full-time university professors, and that includes both tenure and non-tenure- track positions. The remainder of the 40 percent are employed in positions such as part-time professors, research and teaching assistants, college instructors, administration and support staff (e.g. career services professionals), and postdocs.

Just over 60 percent of PhDs go on to work in other sectors such as industry, government and non-governmental organizations. However, they frequently have difficulty transitioning out of academia and knowing how or where to look for other opportunities, the report noted. Many also encounter negative attitudes from potential employers about the value of hiring a PhD graduate.

Those employers that do hire PhD grads “are actually very positive about them and feel they bring a lot of value to their organization,” said Jessica Edge, co-author of the report, who holds a PhD in political science. “The challenge is that a lot of employers haven’t hired a PhD so they don’t really know what to do with them. We need to correct the misperception, the lack of knowledge amongst those employers about how a PhD might benefit their organization.”

Those benefits include great research and project-management skills, said Dr. Edge. “They can help business interface with universities and academia. As a personal aptitude, PhDs are extremely hard working. They are driven and focused. They know how to take a huge problem or issue and break it down into manageable steps and address it.”

Dr. Walker, who was interviewed by the Conference Board for its recent study, ended up applying to the federal government’s Recruitment of Policy Leaders program and worked for three years with the Public Health Agency of Canada. She then segued to Mitacs, a national organization that provides research and training opportunities for graduate and postdoctoral students.

“In Canada, unlike the U.S. and unlike most of Europe, we have less knowledge or openness to understanding the breadth of ability and skills that PhD holders can bring,” said Dr. Walker. “So our industry side and not-for-profit sides hire fewer PhDs than those countries.”

Not only do Canadian employers hire fewer PhDs, we also produce fewer of them. The report found that there had been “significant growth” in the numbers of PhDs granted by Canadian universities – increasing by 68 percent between 2002 and 2011. The number of students enrolled in PhD programs also increased by almost 73 percent. But those numbers still lag other comparable countries. Dr. Walker said that’s a problem.

“Countries such as the U.S., U.K., Finland, Sweden – countries that are at the top of the world rankings when it comes to these macro-economic measures like competitiveness, labour productivity – produce more than twice as many PhDs per capita than we do in Canada,” she said. “So we should continue to produce PhDs at an increasing rate … and help them to transition from academia into their careers by providing the opportunities and increasing the awareness on the receptor side of how valuable a PhD can be.”

On the positive side, once PhDs do transition into a job, inside or outside of the academy, it pays off for most. The Conference Board report “shows they make more than other types of graduates,” said Dr. Edge. “We calculated about $13,000 more per year than master’s graduates, and that’s assuming PhDs earn nothing during the course of their PhD, which we know is not the case at all, so in reality it’s probably a bit better than that. They also have lower unemployment rates than other types of graduates.”

However, the report also noted that PhD students study longer and therefore take longer to close the earnings gap; they also appear to have lower earnings than their peers in the U.S. Moreover, the report said there remains a “striking” earnings gap between male and female PhD holders.

Susie Colbourn said she undertook her PhD studies – in history at the University of Toronto – with a lot of passion and a healthy dose of realism. Now halfway through her program, she is frustrated by the perceptions of employers and some media that question the value of a PhD. “A lot of students decide to take on graduate work because they love it and they’re excited by the fact that they can receive funding to just do what they want to do for a degree program,” she said.

“I think it’s good to be honest and open about the fact that we should temper people’s expectations before they pursue graduate work. There are very serious questions about whether it’s worthwhile to produce as many PhDs if there are only so many tenure-track jobs. But, that also makes an underlying assumption that the only way to be successful with a doctorate is to walk into a tenure-track job. I don’t necessarily think that’s true.”

She also felt more can be done to change those perceptions. “We need to do a better job of convincing non-academic employers that the training of a graduate degree, be it in history or English or physics or engineering, teaches you valuable skills that you can bring into a workplace and that it’s not simply an apprenticeship to be a professor.”

Brenda Brouwer, president of the Canadian Association for Graduate Studies and vice-provost and dean of graduate studies at Queen’s University, said the challenge now is to collectively do a better job of helping students see how their knowledge, intellect and skills can be used in multiple sectors and environments. “We’ve got to give them a strong foundation – focused knowledge, expertise in whatever discipline they’re pursuing – and give them opportunities to work collaboratively not only with people from other disciplines, but also through community engagement,” she said. “Ramp up the number of local and regional partnerships. That’s what students are asking for. They’re seeking more interdisciplinary, ‘real world’ experiences.”

Ms. Colbourn at U of T doesn’t know what her career path will be, but she said she’s still “very happy” with her decision to pursue a PhD. “It may never lead to a tenure-track job. I hope it does, but if it doesn’t then I’m open to that possibility. I think that there are lots of opportunities to use a history education and my philosophy is to take them as they come.”