Jared Wesley earned his PhD in political science from the University of Calgary. His career path has taken him from tenure-track at the University of Manitoba, to senior management at the government of Alberta, and back to academia at the University of Alberta. Find him on LinkedIn, Twitter (@ipracademic), and Flipboard. For an earlier interview with additional reflections, see his previous Beyond the Professoriate Q & A.

What did you hope for in terms of employment as you completed your PhD?

What did you hope for in terms of employment as you completed your PhD?

My eyes were firmly fixed on a university job. It wasn’t until years later that I realized I was on “the golden road” when it came to academic employment. Like many doctoral students, I had been tops in my class from kindergarten through my Master’s, and the tenure-track seemed like the natural next step. And like many doctoral students, I had swept aside warning signs that the road to tenure was full of barriers. I was overconfident and naive. When told that only one-in-four PhD graduates landed a tenure-track position, I felt sorry for the other three. (The figure is now closer to one-in-five, but I still see that “Top Gun” mentality among many doctoral students today.) It was only after I left academia that I realized just how privileged my path had been.

What was your first post-PhD job?

Looking back, I was extremely fortunate to be hired as an assistant professor of political studies at the University of Manitoba. Mine was the last tenure-track hire in Canadian politics in over four years, thanks to the 2008 economic downturn that wreaked havoc on government and university budgets just weeks after I got the keys to my office.

At the time, I considered it my “dream job”: teaching and researching politics in the province I grew up. I was even luckier to have been given that opportunity while still ABD, even though it meant launching my teaching and research program while finishing my dissertation and living in a different province from my partner. Eventually, though, things came together. My partner joined me in Winnipeg, and we got married. I finished my PhD, and transformed my dissertation into my first monograph, Code Politics. Professionally, life was great.

How could you leave a “dream job”?

I can’t say it enough: I came from a very privileged position. I had received (not earned) a lot of breaks from childhood and adulthood. As the saying goes, I started life on third-base and hadn’t hit a triple. That privilege gave me the luxury of reflecting on what I wanted out of life. Unlike so many people in grad school and even more in society at large, I didn’t have to worry about where my next paycheck was coming from, and could literally afford to walk away from full-time employment if it meant finding something better. From that vantage point, I realized that – as much as I loved my day job, and as wonderful as my colleagues at the U of M were – it was just that: an occupation during the daylight hours (a few evenings and weekends notwithstanding). I wanted something more.

Tenure track? What more could you ask for?

My partner and I spent a lot of time together and individually trying to answer that question. We both loved our jobs and our colleagues. Yet we reached the same conclusion: the number one factor for us was where we wanted to live. We wanted more than anything to return to Edmonton, where we had met in undergrad and fallen in love with the city.

This was a difficult realization for an academic, given that location is one of the few variables over which you have no control. Tying yourself to a particular province, let alone city, severely narrows your options for tenure-track employment. In my case, this meant hoping that a vacancy appeared at one of only two universities, in my field of expertise – a very unlikely development given the state of the economy. In short, leaving the University of Manitoba meant leaving behind a career in academia, and I knew it.

How did you make the decision to leave academia?

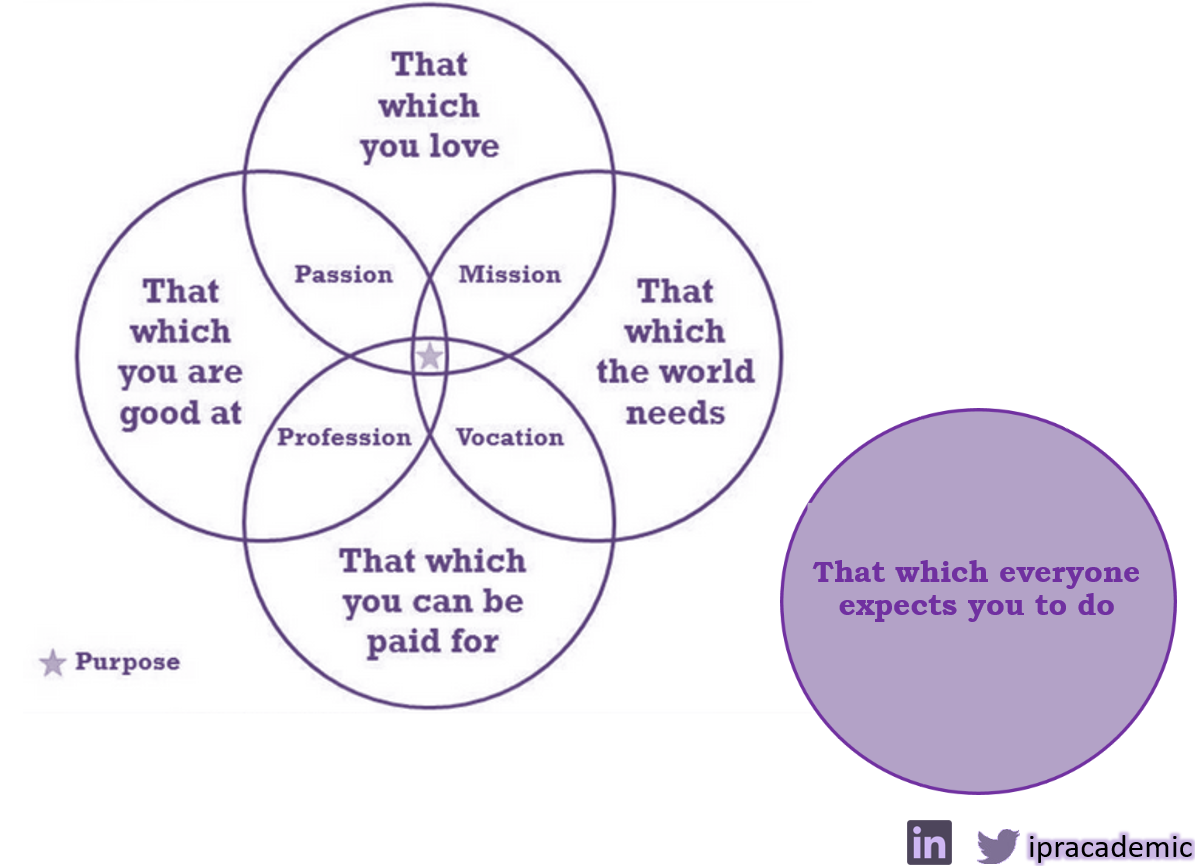

As we talked it through, I noticed we kept coming back to four main questions:

- What are we good at?

- What can we get paid for?

- What would we like to do?

- How can we make a difference?

It was only years later that I realized we were trying to find what the Japanese call ikigai – roughly translated as our reason to get up in the morning. In one memorable exchange, I recall my partner telling me – in no uncertain terms – that my makeshift plan to quit my job and move to Alberta to become a barista would meet none of those important criteria: I wouldn’t be good at it, no one would hire me, I wouldn’t be passionate about it, and it wouldn’t serve a grander purpose.

As we continued our conversations, I found the notion of “public service” was very important to me, and that continuing down that career path would prove very rewarding.

How did you get started on your post-ac job search?

Finding my ikigai was a crucial first step, as it narrowed my field of search to government and non-governmental organizations. Unfortunately, I would be searching in a province where I had no network. I started cold calling people, to no avail. Eventually, I reached out to a former summer job boss in Manitoba, and asked him if he could set up a meeting for me with his counterpart in Alberta. This worked, and I drove 1,300 kms across the country for a 15-minute coffee meeting.

At the time, I didn’t think it would come to much. The government, like the university, was under a hiring restraint and there were few jobs being posted. Four months later, though, I got an email out of the blue, inviting me to apply on a new position in intergovernmental relations. I did, and – after another cross-country trip to interview – landed the job.

What was it like leaving academia?

It was jarring, at first. To go from being my own boss to being a bureaucrat was an adjustment. Yet, I came to love the structure, the routine, and the people. So much so, in fact, that I consider my various public service positions to be “dream jobs” unto themselves.

Indeed, looking back, I realize this was one of the least stressful stages in my career. There was pressure, to be certain. But it was very different from the internal pressures I feel in academia.

How is the public service any different?

To boil it down to a single emotion, I never once felt guilt while working in the public service. I feel it all the time as an academic.

As one of my mentors put it, as a professor, I feel guilty for taking work home each evening or on the weekends, because it means stealing time away from my family. Yet I also feel guilty when I don’t take work home, as it means fewer publications and grant applications.

I never experienced that sense of guilt in my six years in the public service. I had the privilege of serving in senior management positions in intergovernmental relations (directly advising over a dozen cabinet ministers), cabinet coordination (preparing briefings for our premier), and learning and development (developing programs for over 40,000 civil servants). Yet my work was never really my own.

I’m not suggesting I felt no personal accountability for, or pride in, my civil service duties. Accountability lies at the heart of public service, and I can count on one hand the number of civil servants I’ve met who lack a sense of pride in what they do. Nor am I saying that my work lacked impact. My most meaningful professional moments have all been in service to the province of Alberta.

What I mean is this: there’s an ironic sense of freedom that comes with being part of a highly structured organization like government. It allows you to serve someone other than yourself. For all its merits, I’ve found academia to be far more competitive and self-serving enterprise, especially pre-tenure when the pressure to publish is highest.

Did you sever ties with academia, entirely?

Oh, not at all. As an adjunct professor a the University of Alberta, I kept teaching and researching while I worked in the public service. It was period during which my partner referred to me as a “recovering academic” – I fell off the wagon once a week to lead an evening seminar, and was known to wake up early to read and write before work. With forgiving editors, generous co-authors, and supportive leadership at the University of Alberta, I was able to work in two professional worlds for over six years. I even managed to publish a few co-authored and edited books in the process. I later adopted the term “pracademic” to describe my role.

What is “pracademia”?

I’ve researched and written on this previously, but in essence pracademia is a culture – a network of people who appreciate the benefits of solving real-world challenges by combining practitioner and academic perspectives. A pracademic is someone whose work as a practitioner draws heavily on academia, or whose academic work is closely connected to the practitioner’s world. Pracademics may work within either community, move back and forth between them, or straddle the divide. To be blunt, pracademia allows practitioners to get off of the dancefloor and onto the balcony, while allowing academics to get out of the balcony and onto the dancefloor. Both communities benefit from a more holistic perspective.

It sounds like you enjoyed the public service. Why return to academia?

It’s true. I loved working in the public sector by day, and teaching and publish outside business hours. In fact, the decision to return to full-time academia was even more difficult than the one to leave it. When a tenure-track, associate professor position was advertised at the University of Alberta – to help set up a new graduate program in public policy – I nearly didn’t apply. I loved my professional life so much.

I received three pieces of advice that made the biggest impact on my decision to return to a full-time academic career. The first was to follow the Kaleidoscope Career Model (KCM), and choose the path that led to the ultimate combination of authenticity, balance, and challenge (A-B-C). According to KCM, when approaching a potential career shift, you should ask yourself three questions:

- Authenticity – Which route will allow me to be my authentic self at work, as opposed to adapting my personality, values, style, or approach?

- Balance – Which path will provide me with the most flexibility and support to pursue objectives outside my professional life?

- Challenge – Which choice will push me to my limits, and help me expand my potential?

A second piece of advice was pertinent for someone like me, at the midpoint of my career. Rather than focusing on the next job, ask yourself: “What do you want your last job to be?” Knowing that can help determine which option will best help you to reach that ultimate goal.

The third bit of guidance was by far the simplest: “Ask two people who know you best: ‘Which route is best for me?’ They won’t disagree.”

In all three areas, I found a return to academia the best choice for me at this point in my life. But, it was close.

Do you see yourself returning to the public service?

If I find my ABCs are out of alignment – that I’m not being authentic, if am out of balance, or if I’m feeling unchallenged – I could see myself seeking new opportunities in the public sector. I’m a pracademic, after all.

What advice do you have for post-PhDs in transition now?

As I said earlier, I’d encourage them to invest the time to find their ikigai and focus on their ABCs.

I’d also say: try not to let your perceptions of other people’s expectations to drive your decisions.

As I was leaving academia, feeling guilty for abandoning my department after they had invested so much in hiring me only a few years earlier, one of my colleagues reminded me of an old maxim: “you wouldn’t worry nearly as much about what other people think about you if you realized how seldom they do.”

Leaving academia for another career path isn’t a sign of disloyalty, it isn’t quitting, and it doesn’t mean abandoning those people who have supported you along the way. Those people who know you best will support you most in your quest for purpose, authenticity, balance, and challenge. Reach out to them, and to others who have made the transition, if you need a hand.

Outstanding article Jared! We grow when we push ourselves to our edges….keep growing!

If you want a good career, be it academia or otherwise, you have to hustle during your PhD. Be productive, work on something with practical applications (direct or implied), network, garner as many awards and accolades as possible, be passionate, never fall into the trap of self-entitlement, and stay optimistic.

No one should be surprised or even dismayed that there isn’t a tenure track position for everyone, expecting an exponential growth of profs is absurd.

Thank you for sharing your experience. I like the concepts of ikigai and the pracademic. They resonate with me. I have a PhD and chose the administrator path. I still see the need to write articles and do research even though they are not part of my position description. I wish you all the best in your future endeavors.

What a ridiculous about of privilege to be able to land the job you want in academia, walk away, and then get it again. Writing here trying to advise graduate students who will likely never have those same opportunities, and patronize them with some Japanese philosophy, is incredibly tone deaf.

This column is just bad.

“Les” : Thanks for your feedback. I spoke at length about privilege and luck. Too few of us in academia do, so your criticism is misdirected if not misplaced. It’s saddening that you find non-Western philosophy “patronizing.” This said, coaching graduate students to wallow in debt, boredom, angst, and malaise as opposed to finding ways to pay bills, use skills, find fulfilment, and make a difference is certainly another way to go. There’s no shortage of #quitlit out there for that sort of approach. There’s also no shortage of grad students who naively “follow their dreams,” thinking everything will simply work out for them. That’s not how it turned out for me. Mine’s been a windy path, and I’ve tried my best to find ikigai and ABC along the way. I hope you and other readers will find the same.