It was minus 20 outside, a typical winter night in Sudbury, Ontario, when my father, Frank Smith, sat the family around the kitchen table and unveiled his new job plan. After years of teaching chemistry at Laurentian University, including five years as dean of graduate studies, he’d decided to change institutions. “Not a big deal,” he said. “Your mother and I are going to Qatar. It’s about 10,000 kilometers away and one of the hottest, driest and richest countries on earth.”

Dad had signed a contract with the Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar (known as WCMC-Q) to teach undergraduate chemistry. But what was intended to be a three-year stint overseas turned into a long-term move and life-changing experience for both my father and mother. Three years became six, then 10. The move also had a positive impact on my life, providing me the opportunity to make many visits to the Persian Gulf region.

My first trip to Qatar was in December 2002, and I was unprepared for the grueling, 20-hour, connection-ridden flight. Jet-lagged, I dragged myself through the sliding arrivals doors and crowds of migrant workers and found my father on the other side, tanned, chirpy and wearing a Hawaiian shirt. “Hey there, Sport,” he said. “Welcome to Doha!”

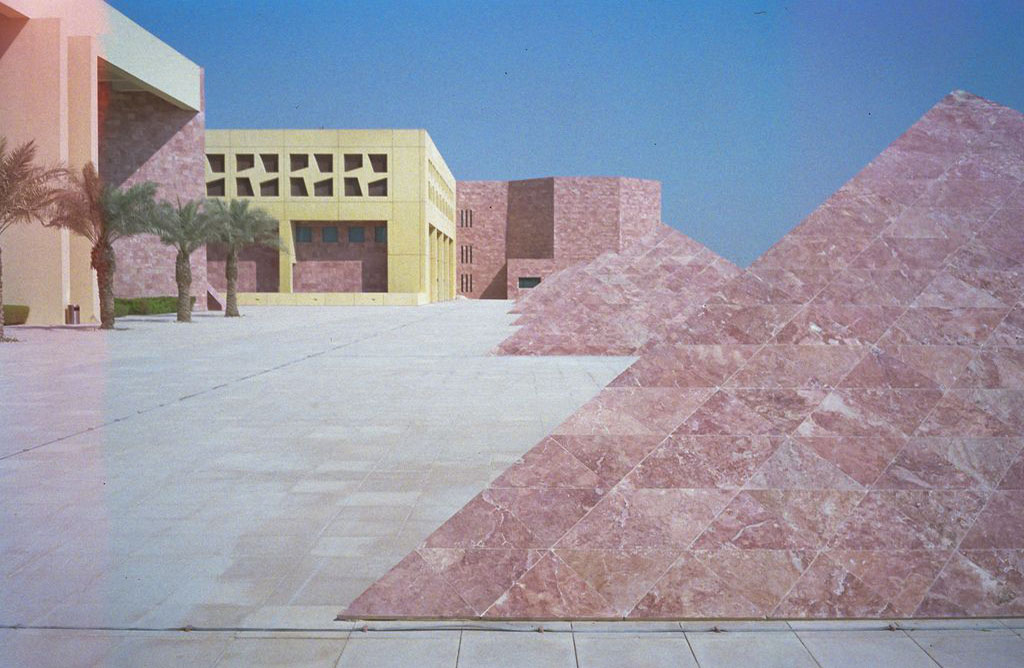

Qatar is a country that is always working to improve itself, as seen by all of the construction sites spotted around the city of Doha. Photo by Sam Agnew.

On the drive to the compound where my parents lived, I admired the Doha skyline (a towering work in progress) while Dad regaled me with stories about the university. He was energized and excited to be part of something new. The Weill Cornell campus in Qatar was the first American college to offer its medical degree outside the United States, and Dad was teaching the first group of students admitted into the program, which includes two years of pre-medical and four years of medical training.

“You won’t believe how smart and keen the students are,” he said, noting that they came from all over the Middle East as well as from Bosnia, India, Nigeria and other countries.

At the time, I was an undergrad at Acadia University in rural Nova Scotia and couldn’t imagine what it would be like to go to school in Qatar. Could male and female pupils sit together? And, I wondered, do the women have to wear headscarves?

Some of the schools in Doha do segregate the sexes and have strict dress codes, my father explained. But at Cornell and the other international universities the classroom and teaching dynamics are similar to those in North America. However, the men and women do tend to sit separately in the classroom, and many female students choose to wear the abaya and hijab or niqab. It is also quite common for male students to wear traditional Arab clothing.

Suddenly, the strident sounds of car horns and screeching tires interrupted the peaceful drive. Up ahead, traffic was at a standstill. “We could be in for a bit of a delay,” said Dad.

All around us was a spontaneous eruption of joy. Qataris climbed onto the roofs of their Toyota Land Cruisers and were dancing and waving the national flag. Others, mostly white-robed teenagers, set off firecrackers. Black smoke and the stench of burnt rubber filled the air as cars did donuts in the street. “What on earth’s going on?” I asked. Dad glanced out the window calmly, as if this was a regular occurrence, and said, “Looks like Qatar won the soccer match against Saudi Arabia this evening.”

The following morning, after a restless, air-conditioned sleep, I explored the Al Jazi Gardens compound. It was lush with exotic plants, and dotted with outdoor swimming pools, tennis and squash courts, a soccer pitch, large gym and steam room. The cute winding roads linking the housing units were swarming with kids on bikes and skateboards. Uniformed police officers with submachine guns guarded the front and back gates as a steady flow of families in SUVs entered and exited the compound.

My parents’ two-floor house was spacious and had a small backyard with a garden and two kittens that Mom had rescued. When I peeked into the kitchen, I saw an impressive selection of wines. “Is this legal?” I asked, holding up a bottle. Dad explained that expatriates could apply for a liquor permit, allowing them to buy booze at a reasonable price from a store on the outskirts of Doha. “The big hotels, like the Ritz-Carlton and Four Seasons, also sell alcohol,” he said. “But it’s about ten bucks a beer.”

That afternoon, Dad took me to Education City. Not far from the malls and five-star hotels, this section of Doha is devoted to higher learning. “Looks kind of empty,” I said as we passed endless expanses of dried up seabed and desert shrubs. “Just you wait,” replied Dad, defensive of his new home. “In a few years Qatar will lead the Gulf states in education.” He then pointed to a large pile of rock and sand and said, “That’s going to be the largest teaching hospital in the Middle East.” Eventually we arrived at a school, the Qatar Academy, part of which Cornell was renting while its campus was being constructed next door – the massive ovoid lecture halls, which would become the signature element of the Cornell medical building in Qatar, were already in place.

Inside, Dad introduced me to his colleagues. Many were from the United States and had previously worked for Cornell in New York. Turning a corner, I bumped into a towering man with a buzz cut named Mike Smith, a Vancouverite and former chair of biological sciences at Simon Fraser University who had moved to Qatar because he couldn’t stand retirement. “So this is the heir apparent,” said Mike, slapping me on the back. Mike became my friend and mentor, editing my honours thesis and helping me choose a PhD supervisor and ultimately a postdoctoral adviser. In time, Cornell’s Qatar campus would attract more Canadians, including Kevin Smith, a former chemistry professor at the University of Lethbridge who moved to Doha with his wife and young children, and Michael Pungente, who was a chemistry prof at Lakehead University before coming to Qatar.

Further down the hall, I met the teaching assistants. Most of them had undergraduate degrees from Cornell and were hoping the Qatar experience would help them get into a top medical school back home. They gave my dad a big friendly hello and started hassling him about his fitness – in the evenings on the compound he was teaching them to play squash, and they’d already started to surpass him in ability.

It was obvious to me that Dad’s co-workers were good friends and regularly spent time together outside of work. This sense of unity and rapport within the university and expatriate communities was a recurring theme throughout my visits to Doha. In fact, Mom and Dad were much more social than they’d been in Sudbury, frequently attending parties and having friends over for dinner. Later that week, I accompanied a couple of my parents’ new friends to a New Year’s Eve bash hosted by a group of Newfoundlanders from the newly opened College of the North Atlantic in Qatar. The mix of rum, plaid shirts, cribbage and hockey talk made me feel like I was back in Canada.

Over the next eight years, I celebrated every Christmas and New Year’s in Doha. During this time, I watched Qatar grow from a country that few had heard of to a world player. I saw Roger Federer smash aces at the Qatar Masters and distance runner Gebrselassie set a world best on the roads outside Al Jazi Gardens. And I rejoiced with thousands on the Corniche after Qatar was named host of the 2022 World Cup.

I also formed many close friendships, and some of my friends motivated me to pursue a career in science. For instance, Cornell geneticist Tonie Blackler inspired me with stories about his friend and Nobel laureate Barbara McClintock. Research whiz Joel Malek showed me the ins and outs of genomics as he assembled the date palm genome in a lab down the hall from Dad’s office.

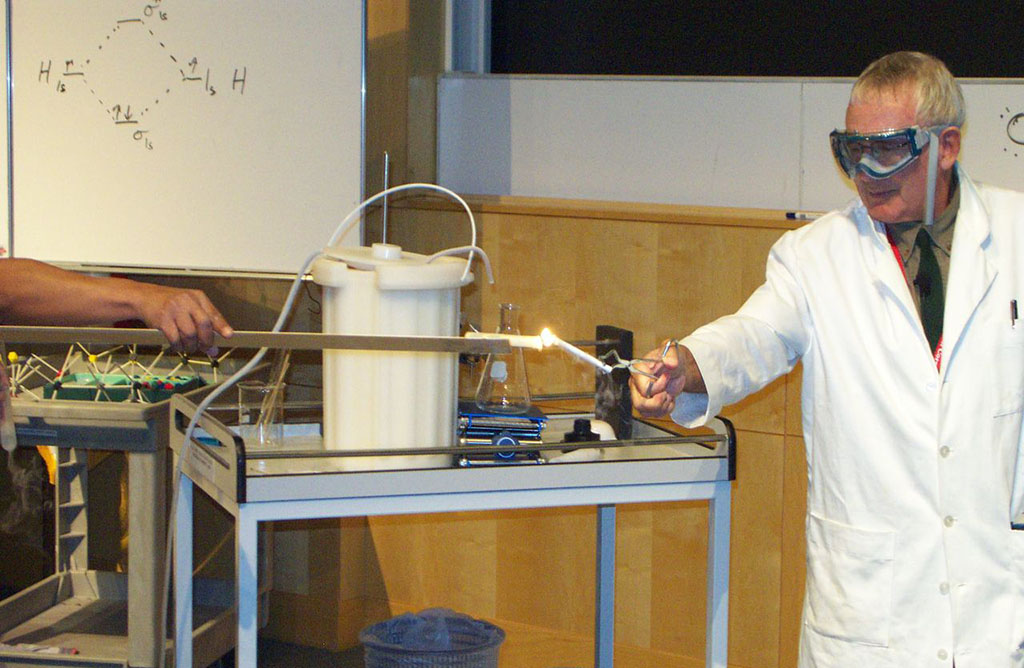

One of the most memorable people I met in Doha was Jim Roach, who co-taught first-year chemistry with Dad. Jim was obsessed with cockroaches. His desk, office shelves and sometimes even his shirt were covered with them. Fortunately, they were all plastic replicas. Jim also had a passion and talent for undergraduate teaching. In class, he wore a tool belt that contained chalk, erasers, markers, laser pointers and, you guessed it, rubber cockroaches. The students adored him.

Jim had taken a leave of absence from his faculty position at Emporia State University in Kansas to teach in Qatar. He found the job a refreshing change from the competitive, research-intensive environment of a typical North American university. At WCMC-Q, the teaching load is reasonable, class sizes are small and administrative duties are minimal. Jim enjoyed the job so much that he resigned from Emporia and is now a permanent faculty member at WCMC-Q. Luckily, his wife found a job teaching art at a Doha high school.

My friends in Canada often ask me if it was difficult for my mom to live in an Islamic country. It was, but not in the ways one might expect. She could drive and regularly explored the city on her own, never worrying much about covering her hair, legs or shoulders. And when she sat at coffee shops alone reading books, the Arab men never bothered her; if anything they were polite and considerate, often relinquishing their tables so she could have a prime people-watching spot. The hardest part for Mom was leaving behind her life in Canada, where she’d owned and operated a small antique shop for 15 years. In Doha, the swimming pools and shopping malls can quickly lose their appeal and if you aren’t working, the days can be long and boring, especially in the summer and fall when midday temperatures exceed 40 degrees Celsius. Mom took up golf to keep busy and healthy and to meet new people. But for some, the challenge to stay engaged or find a job is too daunting. I met many people in Doha whose husbands or wives had returned home, leaving their partners to go it alone.

On my final trip to Qatar, Dad and I spent a lot of time in Education City, often watching keynote lectures by prominent scientists and writers, including Nobel laureate Sydney Brenner and journalist Robert Fisk. I was amazed by how fast the academic landscape had transformed. “Not so empty now!” bragged Dad as we drove past the campuses of Texas A&M, Carnegie Mellon, Georgetown and Northwestern universities. “Get a load of that,” he said, pointing to a structure beside the teaching hospital.

There I saw what I believed to be the coolest building in Qatar: a convention center modeled on a sidra tree, with massive ascending branches, like arteries, covering the concrete and steel walls. “Why a sidra?” I asked Dad. He explained that the sidra is a tree that can grow lushly in the most arid environments. “And in its shade is where the poets and scholars would exchange ideas.”

Not long after that visit, my father traveled to New York City for a hip replacement. The day before the operation he calmed his nerves by exploring the streets around the hospital. Walking past a coffee shop, Dad heard someone yell, “Hey, Dr. Smith!” Turning, he saw a young man in scrubs – it was one of his first students from Qatar who was doing his medical residency in New York. They talked for a few minutes, and before parting, the student complimented Dad on his teaching.

The hip operation was a success and Dad can now go for daily walks along the shores of Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia, where he’s retired and where Mom runs a small antique shop.

David Smith is an assistant professor in the biology department at Western University.

Dr. Smith is clearly speaking only to Canadians who have an exceedingly poor knowledge about the Gulf States and who drink rum, wear plaid shirts, and play cribbage and hockey in this nauseatingly Orientalist and ethnocentric “article.” Publicizing his poor geographic knowledge (he assumes most readers have never heard of Qatar until recently) and sharing his disturbingly simplistic assumptions about the status of women in all “Islamic “ countries (until his mommy told him otherwise!) tells us very little about Qatar but a lot about the author’s sensibilities and prejudices!

What a delightful article! Having known Frank Smith for over ten years I can only wish him well and commend his son for writing this article. I, of course, cannot comment on Peter’s knowledge of the Gulf but as someone who started his employment with WCMC-Q at around the same time I can assure you there was not much to be gleaned about Qatar from afar for non Far East Studies graduates. I must say that I flew in with very little foreknowledge despite extensive internet searches. There simply wasn’t much online circa 2002 about Qatar. And I’m not even a rum-swilling plaid-shirted Canadian!

I should probably state that I was reading this article because it is many of my photos that accompany it. I live in a mainly Arabic-speaking compound in Doha and frequently explore the country looking for new places and new people. I have met a number of extremely friendly and well-educated Qataris here and I assure you that there is nothing in this article that most of them would find offensive. Many of the local population shop in London, Paris and New York and send their kids to US, UK and Canadian schools for college and university. In fact, addressing this is one of the motivators for the government’s investment in Education City. All are familiar with at least some western TV and movie fare. In any case, Qatar is a place where nine out of ten people are not from here. People here understand that incoming westerners have some questions and uncertainties about the place. For the most part I have found them to be far more tolerant and understanding in their treatment of those ignorant of their culture than my esteemed fellow commenter, Mr. Tremblay.

Finally, this is a Canadian academic journal. Surely rum-swilling Canadians are the correct target audience. As long as this is done without insulting or disparaging the people of Qatar (of whom I have always known Frank Smith to be a great admirer) then I’m not sure how the article should have been written differently.

Surely, the article was intended for ‘Travel & Leisure’ magazine.

Well done! Dr.smith you write a nice article.you ex plane your journey in simple word and cover each and every points which is good.your journey to Qatar(Doha)is looks like superb.This is a Canadian academic journal. NO doubt rum-swilling Canadians are the correct target audience.This is done without insulting the people of Qatar then I’m not sure how the article should have been written separately.