A funny thing happened to Julian Haladyn while researching boredom and art. He got excited.

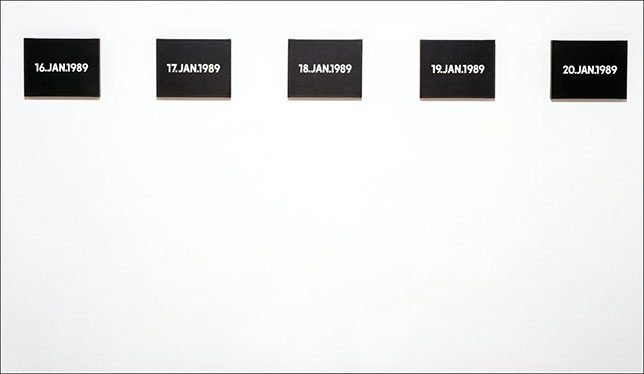

The dull subject was conceptual artist On Kawara’s Today paintings, a series of hundreds of rectangular, solid-coloured canvases – he aimed to make one daily – featuring the day’s date in white. “It was a very boring experience. Your eyes start to glaze over,” says Dr. Haladyn, an OCAD University lecturer, of attending a Kawara exhibition in person.

Dr. Haladyn was doing research for his 2012 PhD thesis, and it was during that work that he came across the image of a Kawara painting featuring his birthday – different year, but the right day. He was so thrilled he called his partner over.

That moment of excitement perfectly fit his evolving theory. Dr. Haladyn, who turned his thesis into the 2015 book Boredom and Art: Passions of the Will to Boredom, thinks Kawara and other artists know their repetitive paintings, long videos and uneventful performances are snooze- inducing; they expect boredom to trigger anger, mind-wandering or personal revelation. “These are moments of vision,” says Dr. Haladyn.

We all get bored, and not just while looking at nearly blank canvases. Boredom arrives at work, on rainy Sunday afternoons, in slow lineups at the airport. “It’s so ubiquitous. It’s everyday. It’s something you don’t focus on,” says John Eastwood, an associate professor of clinical psychology at York University.

That may be why the emotion of boredom – unlike love, anger or grief – wasn’t actively studied until quite recently. Now, academics are finding much to mine in its abysses. “It’s all gone into overdrive,” says Peter Toohey, a professor in the department of classics and religion at the University of Calgary and author of the 2011 book, Boredom: A Lively History.

Boredom discourse includes the theoretical via humanities scholars such as Dr. Haladyn; they use boredom as a lens to understand how we seek meaning and deal with technology. More recently, those in the sciences, mainly psychologists, seek the link between the state of boredom and a propensity to become violent, engage in addictions or cause workplace accidents. “These are important real-world problems that people are working on and theorizing about,” says Dr. Eastwood.

Newly achieved critical mass in boredom studies is now inspiring conferences and books, including a recent Canadian anthology that aims to confirm boredom as a bona fide field of study. Indeed, Canada has become something of an epicentre for boredom research as academics here have boldly moved discourse along: as well as pushing for boredom to be designated an official field, they’re creating new psychology tests, fostering an interdisciplinary approach and nurturing the next generation of researchers. They have generated excitement on a topic that, in its very ubiquity, risked never being taken seriously at all.

Through the early 20th century, humanities academics dabbled in boredom through influential texts. Philosophy scholars mined the bon mots of such 19th-century greats as Friedrich Nietzsche, Søren Kierkegaard and the ever-fatalistic Arthur Schopenhauer, who wrote, “Life swings like a pendulum backward and forward between pain and boredom.” Literary critics observed the boredom felt by fictional characters like Jane Austen’s Emma and Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, whose “life was as cold as an attic facing north; and boredom, like a silent spider, was weaving its web in the shadows, in every corner of her heart.”

The topic gained momentum in the social sciences and humanities in the late 20th century with the rise of affect theory, which considers the emotions, and the field of everyday life studies, which ponders daily routines and people’s mental states. Dr. Toohey first wrote on boredom in 1987, and Western University’s Michael Gardiner, a professor of sociology and co-editor of a new anthology on boredom, began writing about it in the 1990s. By 2005, boredom had fully arrived in North America with the publication of two pivotal books: a translation of Lars Svendsen’s A Philosophy of Boredom (published in 1998 in his native Norwegian) and American literary scholar Elizabeth Goodstein’s Experience Without Qualities: Boredom and Modernity.

More recently, science took on boredom, too. “This has been a topic of study [in] everything from philosophy to existential studies. … But it’s always eluded scientific study until the last five to 10 years,” says Mark Fenske, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Guelph.

Evidence-based work on boredom owes its existence to key psychology tests, starting with the Imaginal Process Inventory test of the late 1960s, which measured an individual’s propensity to be bored and to daydream. The 1964 Sensation Seeking Scale was updated in 1978 to include susceptibility to boredom and the Boredom Proneness Scale, created in 1986, was the first to assess exclusively the tendency to feel bored.

Psychology professor Stephen Vodanovich of the University of West Florida began conducting studies on boredom in the early 1990s, including one that showed how participants’ results on boredom tests related to their self-actualization. Canada’s leading boredom-focused psychologists, York’s Dr. Eastwood and James Danckert, a University of Waterloo psychology professor, built on Dr. Vodanovich’s work and that of others starting in the early 2000s. Their research has inspired colleagues, and both run labs that support grad students delving into new facets of boredom.

As boredom bloomed, events followed. The International Interdisciplinary Boredom Conference, held annually at the University of Warsaw, will run for the third time in the spring of 2017. In Canada, symposia on boredom have been convened at U of Waterloo and at Queen’s University. The agendas for these events reveal the field’s engrained interdisciplinary approach, with humanities researchers sharing the stage with scientists.

Then there are the books. This past October, Dr. Haladyn and Dr. Gardiner published Boredom Studies Reader: Frameworks and Perspectives, an anthology packed with the who’s who of boredom studies theorists. In their introduction, the editors write that “the study of boredom is a vital avenue of research” and should be considered a valid field of study.

Despite boredom’s history as an academic topic, not long ago such a declaration would have seemed preposterous. “People looked at you like you’re a bit of a nut. In 1987, it was considered downright silly” as a topic of study, says Dr. Toohey, recalling the reaction to his first article. He had to talk his editor into publishing his boredom book and was told it would never sell (it did, in seven languages). Dr. Vodanovich recalls sending an early paper to a national conference and getting a written reply from the organizers: “Who cares?”

Dr. Danckert didn’t apply for funding for a boredom-specific study until 2013, while he built up a track record. “It’s not risky research,” he says, “it’s just not mainstream.” Dr. Eastwood agrees: “It’s still challenging to situate your work in a framework that makes sense to reviewers and funding agencies.” He now has funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council as well as from the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre, which supports his work linking proneness to boredom with problem gambling.

In those early years, many of these researchers stuck with this oddity of a topic for personal reasons. Dr. Gardiner says his previous research only partly led him to the topic: “It came more of out of the realm of personal experience. I was often bored, in both work and life generally.” Dr. Toohey was motivated by his own personality and hoped his 2011 book would give him more coping tools – but, he says, “I failed. I’m still suffering.”

Dr. Danckert, too, had a personal motivation. His brother suffered a traumatic brain injury in a car accident at age 19 and after that complained of frequent boredom. Dr. Danckert worked with people with brain injuries while doing his PhD in his native Australia, and he started asking them if they got bored often. “They would almost jump out of their chairs. It was important to them and no one had asked.”

Humanities researchers digging into boredom often cite Dr. Goodstein’s theory, explained in her 2005 book, that boredom is a modern phenomenon. She writes that while people must have felt bored in the past, life after the industrial revolution can lack meaning, and boredom in this context is a more profound experience.

This theory underpins Dr. Haladyn and Dr. Gardiner’s work and their anthology, which includes essays on violence, photography, power and online dating. Sharday Mosurinjohn, associate professor in the school of religion at Queen’s, contributed a piece about texting and “overload boredom,” the concept that when bombarded with too much, we lose a sense of meaning and become bored. She delves into the allure of texting’s back-and-forth monotony: “It’s something we find really boring but it’s also evidently meaningful as we keep doing it.”

Not all humanities researchers agree with the link between modernity and boredom. Dr. Toohey argues that just because the words “boring” and “boredom” didn’t appear in English until the 19th century doesn’t mean the experience didn’t exist. “Emotions are universal,” he says. “Animals can be bored.”

There’s little debate, though, about the central theory driving boredom research across disciplines: that the state of boredom, like pain, offers a warning sign. “Boredom shows you something is wrong,” says Dr. Eastwood. “Think about it as a signal or a cue to identify a problem. Then the question is how we solve that problem, do we solve it in maladaptive ways?”

Building on this, much boredom work in psychology labs asks who’s bored and why, and which characteristics lead people to make unhealthy choices to solve the problem. Dr. Danckert’s lab has found that people with “high locomotion,” in that they move easily between tasks, are less likely to get bored, particularly if they’re accepting of their choices.

Psychology labs may also measure hormone levels and determine which parts of the brain fire up when someone is bored. Daniel Smilek, a professor of psychology at U of Waterloo who specializes in mind-wandering (or daydreaming), has done work for the transportation industry to better understand how locomotive engineers cope with sudden, critical events after long, dull stretches of nothingness. “When you have to do repetitive work and it’s understimulating you, you tend to experience boredom and disengage. When you’re doing safety-critical work, that becomes very dangerous.”

However, in this emerging field, some of the foundations remain unsettled. First, there’s no universally accepted definition. “If you want to study the effects of boredom in the lab, you have to be able to measure it. You can’t until you’ve defined it,” says Dr. Eastwood. In a 2012 journal article, he, Dr. Fenske and Dr. Smilek proposed a definition: “the aversive experience of wanting, but being unable, to engage in satisfying activity.” This wording has met with general approval, but not widespread acceptance. Humanities scholars, in particular, resist pinning it down.

In psychology, boredom tests each use their own definition, but also test for different things. Moreover, no one is sure the tests are reliably assessing what they claim. Dr. Eastwood wants further definitions to differentiate between “state boredom,” being bored in that moment, and “trait boredom,” the tendency to be bored often. To that end, he and a group of graduate students developed the Multidimensional State Boredom Scale and published its parameters in 2013.

In the process of studying boredom in the lab, psychologists have found unexpected things. For one study, Dr. Danckert’s lab made the participants bored by showing them a video of two men hanging laundry, which bored them after eight minutes. They were then given routine attention tasks to do, but a follow-up test revealed that these attention tasks were even more boring than the laundry video.

Researchers have also found that PowerPoint presentations and online lectures bore students, and quickly. One lab uses online lectures from Yale University to bore test subjects in just seven minutes. Another study, conducted in the U.K., put participants alone in an empty room as a way to bore them – but the participants loved the experience.

This busy, rich field has momentum. While longtime researchers once met with raised eyebrows at cocktail parties, the general public is now hungry for boredom talk, as is the mainstream media. “I get calls every three or four weeks to talk about it,” says Dr. Toohey. Being bored is a universal experience and everyone wants to understand it.

Since this interdisciplinary field is still in its adolescence, rapid growth will mean important discoveries, more accidental revelations, but also uneven research quality. After all, since everyone gets bored, pseudo-academic essays already abound on the topic. Asked where he sees work in boredom heading, Dr. Toohey says, “I think that there will be too many books and everyone will let forth with a great groan.”