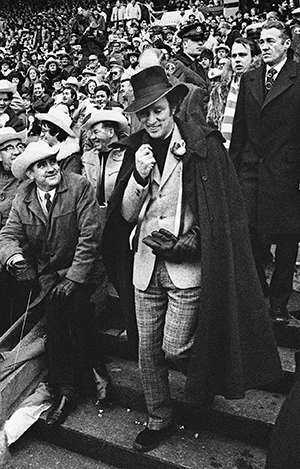

Photo courtesy of Peter Bregg/Canadian Press.

The dull roar of plastic computer keys clicking in the lecture hall at the University of British Columbia stills for a moment as Canadian history professor Bradley Miller flashes a picture onto the screen behind him.

It’s former prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, flamboyantly decked out in a cape, white jacket with a rose pinned to the lapel and a 19th-century dandy’s hat – an incongruous sight at that most high-testosterone of events, the Canadian Football League’s Grey Cup championship of 1970.

“You have to admire a guy who would do this,” says Dr. Miller as an aside in the middle of his lecture on the tumultuous political world of Canada in the 1970s. The 90-some students in the large hall laugh then resume their furious typing as he continues, “The 1970s was a terrible decade for the old dominant political parties…”

Dr. Miller’s decision to show that picture, an iconic image frozen in time, has a strategy behind it. The picture is a moment in Canadian history worth storing in students’ memory vaults. It says something about what Canada was at that moment in time.

In its small way, the picture performs the same function as the entire unusual course he’s currently overseeing. The course, prosaically known on the calendar as History 235 (PDF), captures the spirit of a nation in one flash – just like each one of the lectures in this course. The second-year survey course spanning settlement to the 21st century was remade three years ago and transformed from the standard overview of Canadian history to a new approach with a new title, “History of Canada: Moments that Matter.”

But it wasn’t just the content that got reshaped, it was also the method: instead of one instructor flying solo on the survey, it’s now taught through a collaborative teaching method called sequential teaching. With this approach, one professor oversees the entire term and generally holds things together. Seven other history professors join Dr. Miller to each deliver lectures on topics they passionately believe are key turning points for the nation.

“Each lecture has to come to a productive and provocative point”

“Survey lectures can be long and encyclopedic,” says Dr. Miller, reflecting on the course a month after the final exam in December. “But with this ‘moments that matter’ frame, it forces you to sculpt each lecture. Each lecture has to come to a productive and provocative point.”

And so there was a lecture last September about British Columbia, Captain Cook and the Indigenous worlds he encountered, presented by professor Coll Thrush, who has researched Indigenous encounters with European newcomers, including the first-hand experiences of Indigenous people who travelled to London, England, from various British colonies.

In October, Tina Loo, a specialist in environmental and Canadian history, delivered a vivid lecture about the role that bison played in the colonization of Canada. (Pemmican, made from bison meat, became a crucial energy source that allowed the fur traders to extend their territory – but more on that later.)

By mid-November, students were hearing about the creation of the new Canadian flag – and a new Canadian identity – in 1965 by instructor Michel Ducharme, who specializes in the history of Quebec. Dr. Ducharme was on leave from UBC at the time but flew in from Montreal to do his part.

Dr. Loo, who is also the outgoing department chair, says the sequential, team-taught approach changes the whole dynamic. A lone professor teaching for a whole term tends to deliver information in a steady, contained way with more thought to making each lecture consistent and connected. It’s different when eight people are teaching.

“When you’re only appearing for two or three lectures, you want to do a great job. There’s a performative aspect to it,” says Dr. Loo. “I do a different job than if I had the students all term.”

For her, the bison-pemmican lecture she delivered, “Why Bison Matters,” was a way to jump into an essential theme about Canadian colonization: how food developed through Indigenous technology allowed European newcomers to survive the environment and stake claims on the land. The early fur traders tried to navigate their new land surviving on items like lard and dried peas. Not only were those food sources heavy to carry in canoes, they didn’t provide much food energy.

of http://homesteadandprepper.com

“There was a limitation in how far west and north they could go with that,” says Dr. Loo. That all changed once they figured out the advantages of pemmican, a traditional food for Indigenous nations in the Plains made with dried meat, melted fat and dried berries. It packed twice as much food energy per kilogram than anything else the Europeans had.

The course has also allowed people in the department to collaborate in a way they never have before. Professors tend to work in a very solitary way, writing alone in their offices, going out alone to their classes. “We rarely engage in collective endeavours,” says Dr. Loo. “I have to say, it was a lot of fun.”

For this course, the whole department pitches in every year, with professors putting in bids to the course leader for a particular moment they’d like to teach and why it’s important to Canadian history. In this way, the department shapes the course as a team. This year, for example, retired professor Bob McDonald successfully made a case to dedicate more time to the First World War – a topic that hadn’t been covered at all in the previous two years of the course. He wound up with a place on the syllabus and a full week in front of the class in October.

As so often happens in the process of invention, none of the eventual outcomes – fun, collaboration, greater theatrical teaching efforts, a chance to show off the department’s expertise in a single course – were the original goals. Like many other traditional academic disciplines, the history department had seen enrolment numbers go down for the previous full-year survey course in Canadian history. Students, it seems, prefer the options that one-term courses give them, but the department wasn’t quite sure what to do about it back in 2014.

As the department’s Canadian history specialists brainstormed ways to revitalize the course together, Laura Ishiguro recalled an undergraduate course that she’d seen put on by University of Victoria professor John Lutz. Called “10 Days that Shook the World,” Dr. Lutz invited colleagues to come to the class to talk about a day they believed changed world history.

“I thought that had a lot of potential,” says Dr. Ishiguro, who pitched a similar idea when she presented a course syllabus as part of her UBC job interview in 2012. Dr. Ishiguro says one big advantage of that kind of course is it helps reinforce a central idea about the nature of history itself, which is that it isn’t solid and immutable – different historians may have different interpretations.

“It turns Canadian history into a series of questions about why we think things matter and for whom they matter.”

“It turns Canadian history into a series of questions about why we think things matter and for whom they matter. What moments mattered most and why – those are questions that demand we interpret the past. Students get this really rich, challenging diversity of ideas about Canada. And they get to see each lecture as an argument,” says Dr. Ishiguro, who led the course the first two years (she was on leave during the 2016-17 academic year).

Of course, one of the concerns for Dr. Ishiguro and others in the department was what the students would think of it all. Students don’t get a warning when they register for the course that it is going to be structured that way. And sequential teaching, the kind of collaborative teaching used in this course, can feel disruptive and disconnected – as though no one is really in charge and no one really knows what the link is between each lecture.

That’s the downside that two UBC researchers found in a 2012 study, after looking at more than 950 students, 17 instructors and nine different science courses that were either team-taught (with two or more professors in the classroom at once) or sequentially taught (multiple instructors each lecturing alone).

Francis Jones and Sara Harris concluded that students had lots of positive things to say about collaboratively taught courses. They liked getting a variety of teaching styles and perspectives, and they liked having experts in specialty fields teaching them. But the “dominant disadvantages identified were adjustment to teaching style and expectations, and confusion and communication issues.”

The researchers found that these problems were mitigated when the course instructors were clear about why the course was being taught collaboratively and put effort into reducing any confusion about course structure. In Moments that Matter, for example, Dr. Miller gives more lectures than any other professor, is present in every class, no matter who is lecturing, and he makes it clear in his syllabus and interactions with students that he’s always available to them. He is the course’s clearly identifiable home base. (As lead instructor, he also develops the syllabus and course assignments, assigns readings and even leads a tutorial group.)

The study found that professors were often more apprehensive about the potential negatives of a team-taught course than the students were – something that the UBC history professors also experienced. In person and in surveys, students have made more positive comments about the Moments that Matter course than negative ones.

“It was easier to see the significance of things, it was easier to remember,” says Cindy Bromley, a 57-year-old communications consultant who took the course last fall as a mature student pursuing a degree in political science and anthropology. Ms. Bromley also took a course on natural disasters at UBC that was sequentially taught by different professors with expertise in thunderstorms, earthquakes, landslides and volcanoes, which provided a similar experience.

“I really enjoyed both the format and the content of this course, especially the structure of why each moment was significant to Canada”

The one downside Ms. Bromley noticed was that students seemed to interact a lot less with the instructors than in other classes, a drawback she suggests may exist because of how difficult it is to build relationships with each new professor to come through the door. Adam Cheifetz, in his fifth year of studies, says he enjoyed the way the course allowed for “different pedagogical styles” and the fact that “you never get an awful or boring teacher for more than two lectures.”

The student evaluations for last fall’s History 235 course echoed these comments by Ms. Bromley and Mr. Cheifetz. Many of the 54 responders raved about the teaching and the structure of Moments that Matter. A typical review: “I really enjoyed both the format and the content of this course, especially the structure of why each moment was significant to Canada. I found the course to be very engaging and put a unique twist on a subject that has the potential to be dry.”

But not every student felt that way. Some feedback reinforced the 2012 study findings: “I found that the inconsistency of having a different prof each class very difficult,” wrote one commenter. Another: “It is nice to have guest lecturers but because everyone has a different teaching style it was sometimes difficult to follow along.”

Still, those opinions were in the minority, and the course will again be taught this fall. Drs. Miller, Loo and Ishiguro are largely thrilled with how well the course has worked out, and not just because enrolment has grown from about 70 students in the former year-long survey course to 99 registered in the 2016 fall-term class. The professors are converts who pass on their enthusiasm for team-teaching to the many professors who ask them about the arrangement and who wonder if a collaborative-teaching approach would work in their fields. For the latter question, Dr. Loo, a committed fan of the approach for history, isn’t so sure it would work for a course that requires students to build on knowledge and skills with each class in order to learn a new step – a math class, for instance.

But Dr. Ishiguro has found strength in numbers when it comes to teaching even a huge subject like Canadian history and doesn’t share Dr. Loo’s doubts. “I talk to a lot of colleagues who are really interested in the model. I think it has a ton of potential. I think you can teach anything like this.”

Frances Bula is a Vancouver writer who covers city life and politics, which often includes the impact of universities on the city.

Selected lecture topics from the syllabus of the fall 2016 Canadian history course:

- Encounter at L’Anse aux Meadows

Taught by Tina Loo - “British Columbia” and Beyond: The Indigenous Worlds of Captain Cook

Taught by Coll Thrush - The Royal Proclamation and the Treaty of Niagara: The Turning Point that Should Have Been

Taught by Paige Raibmon - Loyalism and Liberty after 1776

Taught by Bradley Miller - Local Democracy: Governing Colonial Cities and Towns

Taught by Colin Grittner - Why Bison Matter: Energizing Change in Canada

Taught by Tina Loo - The Persons Case, 1929

Taught by Bradley Miller - “Death So Noble”: The First World War and the Nation

Taught by Robert McDonald - Workers’ Revolt, 1919

Taught by Robert McDonald - The Maple Leaf: Flagging a new Canadian Identity

Taught by Michel Ducharme - Canada and Cold War Crises

Taught by Steven Lee - The Constitution and the Charter of Rights

Taught by Bradley Miller

See the full course syllabus (PDF) for History 235.