Professors Paul, Leo and Louis Groarke are a statistical anomaly. They’re triplets, which occurs only once in several thousand natural pregnancies. They are monozygotic (all of them sprang from a single fertilized egg) and thus they’re identical – clones, you might even say.

The similarities run more than skin deep. All three are philosophy professors: Leo, for much of his career at Wilfrid Laurier University before being appointed president of Trent University last year; Louis at St. Francis Xavier University; and Paul at St. Thomas University.

In a photograph taken at age three, they seem virtual carbon copies of one another sitting atop an old plow wearing the same dark coats and sly grins. Now 61, each has his own distinguishing characteristics. Paul is the most slender and usually wears his gray hair and beard closely trimmed. Leo sports a mustache and Louis, a fuller beard. But on the day we meet, they are clean-shaven and wearing open-necked shirts and dark jackets, no doubt to play up their obvious similarity and hinting at something else they share: a sense of humour.

Guess who’s who, they challenge. And then jokingly offer to pose for a photo as the three wise monkeys – See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil – just as they used to do when they were kids.

Their personalities, they agree, reflect their birth order. Paul, the first born, is the serious and protective older brother, the family historian, and the most private. (He winces at the tape recorder on the table, saying, “I don’t want to be studied.”) Leo, the middle child, is a born conciliator, perhaps presaging his career as a university administrator. Louis plays the role of the happy-go-lucky younger brother and is the extrovert of the group, although, he confides, the outward demeanor masks an inner introvert.

Together or apart, they are seldom at a loss for words, something they attribute to their academic training and their Irish heritage. They will regale you with stories from their childhood while making references to Pascal, Nietzsche and the ancient skeptics. Over lunch in late December at a bistro near Trent’s Peterborough campus, Paul raises the question of whether there is a right and a wrong.

Louis sighs in exasperation: “Of course there’s a right and wrong.”

“And Louis will tell you which is which,” adds Leo with that same grin.

The Groarkes were born in England to devout Irish-Catholic parents and immigrated to Canada as toddlers in 1955. Like many immigrants from the postwar era, the family had come in search of better economic prospects. Their father, John, arrived first but soon had misgivings and wrote his wife, Charlotte, calling the whole thing off. Family lore has it that the letter arrived too late, delayed by bad Canadian weather. With the plans already in motion, Charlotte set off on the trans-Atlantic trip with her four young boys: Michael, the oldest, and the triplets.

Once reunited in Montreal, the family embarked on a cross-Canada train journey to the newly created Doig River First Nation Reserve in the remote British Columbia interior, where John had found a job as a teacher at a government-run, one-room school. They lived in a small house known as the teacherage. It was outside the reserve and separated from the nearest village, Rose Prairie, and from Fort St. John just beyond by the Beatton River, making travel anywhere difficult.

“There’s no tap of course,” Charlotte wrote in an early letter to her mother in Dublin, describing the family’s new life on the Canadian frontier. “John carries water each morning from the river; it’s brownish but good.” In the winter months, he carved blocks of ice and hauled them indoors. Though written much later in time and in a different part of the country, Charlotte’s letters have echoes of Susanna Moodie’s Roughing It in the Bush.

“When I look at the pictures, they feel like a hundred years ago,” says Paul, who edited and published his mother’s missives in an e-book, Letters from Doig. “There wasn’t even a road. My mother had no idea what she was getting herself in for.” He adds, “Of course there were touching moments. But there was a lot of hardship. There were desperate conditions on the reserve – poverty, hunger, even starvation. Of course there were problems with alcohol.”

As well as managing her own household, Charlotte, a nurse by training, delivered babies and ministered to those with measles, tuberculosis and pneumonia. She gave birth to her first daughter, Marcella, at home without any medical assistance. “Nothing here is like my imagination painted it,” she confided.

The isolation wore on her, and after two years John found a new job at a school just outside Montreal. The Groarkes departed Doig River in August of 1957, retracing their cross-country trip, this time by car. To Charlotte, the new modest home that awaited them was “a dream house, all polished oak floors and steel windows” with “running water in abundance [and] electric lights.”

But John seemed restless in the new surroundings. The family later returned to the West, settling first in Edmonton and then in Calgary, where the triplets attended high school and the place they still consider home. Along the way, the Groarkes had four more children: three daughters – Lily, Julie and Mary – and a son, Sean.

The nine Groarke children broke down into two groups: the immigrants and the Canadian-born. For the former, those early years living in the bush “stamped us in a way and made us Canadian,” says Louis. “Although we have spent our adult lives in the East, we all feel pretty strongly about the West.”

Growing up, Paul, Leo and Louis were inevitably the centre of attention. Passersby on the street would stop to stare, take pictures and make a fuss. It was a far cry from the fishbowl the Dionne quintuplets grew up in, but the attention grated at times, especially for Leo.

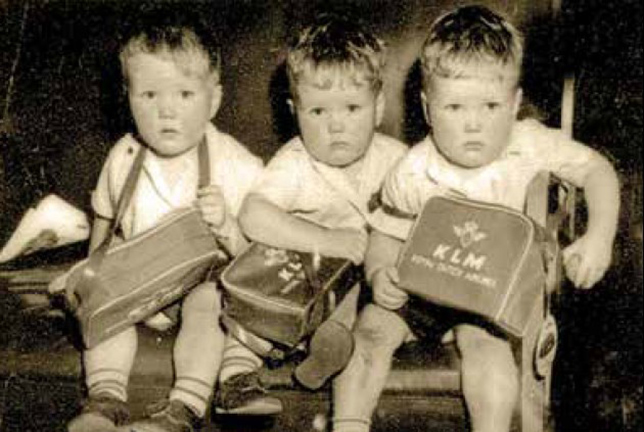

“I couldn’t stand it,” he says. It was like being a part of “a freak show at the circus,” seated next to the bearded lady and the 600-pound man. Their older brother, Michael, probably bore the brunt of it, constantly overshadowed by the younger boys. In Charlotte’s book, a black and white photo taken on their trip to Canada shows the three holding small KLM tote bags. Charlotte had asked the airline officials to include Michael in the picture but they only wanted the triplets.

Few people could tell them apart back then. In grade school, the other children referred to them collectively as Trip (for triplet). So they used the word “singlet” to describe everyone else. They used to know intuitively what the others were thinking and were even able to complete one another’s sentences, although this has diminished with time and distance.

They were competitive, too. “Of course there was sibling rivalry, even jealousy, I suspect,” says Paul – but less and less so as they age. When Paul speaks about Leo’s appointment as president of Trent, he can hardly contain his pride: “The thing about being an identical is that you somehow share in your brothers’ successes. They are your own somehow.”

They continued to be mistaken for one another well into adulthood. Louis likes to tell the story about his wedding. At one point during the evening, his wife was dancing with Paul “all tender like,” believing him to be her husband. It was only when Paul smiled that she realized his true identity. He had knocked out a front tooth in a recent accident. Paul dismisses this as an apocryphal story.

“It’s absolutely true,” insists Louis.

Much more common, they agree, was running into colleagues in airports and university hallways who knew one of the three and were offended if they weren’t acknowledged. Even once they found out the reason why, they often didn’t buy the story.

With 11 people seated around the table, family dinners at the Groarke household were loud and rowdy affairs. In his installation speech, Leo recalled it this way: “I believe that I became a philosophy professor with a special interest in the theory of argument because my parents fostered a lively atmosphere of discussion, debate and disagreement on all things political, religious, personal and philosophical. We debated how late we could stay out on a Friday night, capital punishment, how one should vote in an Alberta election, and Dorothy Day’s radical interpretation of Catholic moral obligation.” Charlotte, now 86, was in the audience, as were Paul and Louis.

Visitors to the house were put off by the commotion, but the Groarkes reveled in it. “It was very Irish – loud voices and people challenging one another,” recalls Leo. “It was great intellectual preparation for something like philosophy.”

Overseeing it all, encouraging it even, was the family patriarch, John. “My father was a very opinionated man and spoke with enormous conviction,” says Paul. “He always had an office in the house buried downstairs, smelling of cigarette smoke and lined with books.”

John had grown up as an Irish-Catholic immigrant in working class Manchester, England and never forgot where he came from. But, to his sons, he was a true Renaissance man, with interests in history, philosophy, literature and religion. (His pet name for the boys: “The unholy trinity.”) John took correspondence courses from the University of Ottawa while the family lived in Doig River and later at the University of Alberta, eventually completing two degrees. In his youth, he had worked as a reporter and served in the war. He returned to journalism later in life, becoming editor of three community newspapers in the Calgary area. His crowning achievement was being banned from town council meetings over something he had written. He went anyway.

When John was nearing the end of his life and confined to a hospital bed, Louis remembers calling him one day and being struck that his father didn’t want to debate. “The life force was ebbing out of him,” he says. John died August 25, 2000, at the age 79.

But it was never argument for argument’s sake. “It’s that rigorous questioning and trying to figure out what’s the ultimate basis of this opinion or this view,” explains Louis. “I think that’s what drew us all to philosophy.” Leo adds, “Both nature and nurture pointed us in the same direction.”

Over the course of their academic careers, each of the brothers developed his own area of specialization. Paul’s is the philosophy of law, Louis’s is ethics and Aristotle, and Leo’s is argumentation. But they actually started down completely different paths.

Leo first tried his hand at chemistry before discovering philosophy. After completing his doctorate at Western University, he spent almost 25 years at Wilfrid Laurier, first as a philosophy professor and then as principal of WLU’s Brantford campus. He moved to the University of Windsor as provost and vice-president academic before taking up the helm at Trent in 2014. In an interview in his office overlooking the Otonabee River, Leo says he prefers smaller institutions where he has the flexibility to stay involved in the academic side of things. He keeps a kayak in the corner for those rare occasions when he can steal away and enjoy a paddle.

Sport was an important part of their youth. All three were competitive long-distance runners and all had athletic scholarships. Louis was the most accomplished and, for a time in the mid-’70s, he held the Canadian title in the 5,000-metre competition. He studied at Colorado State University, initially science, then art and finally art history. He moved to the University of British Columbia to continue his graduate work, where he met his future wife, married and moved to her home province, Quebec. They had six children, and Louis was a stay-at-home dad for many years. (Paul, divorced, has no children. Leo, who has three children, is engaged to be remarried.)

As well as looking after the kids, Louis worked on a dairy farm, ran a shelter for homeless men, taught English as a foreign language and tried his hand at freelance writing. But then he got the itch to return to academia. Philosophy seemed like the natural choice. He graduated from the University of Waterloo and now teaches at St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, Nova Scotia.

Paul, too, came to philosophy later in life, following a distinguished law career. After completing his degree at the University of Calgary, he worked first as a criminal lawyer in that city and then as a member of the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal in Ottawa. Among other things, he chaired a panel on a major pay-equity case.

But he, too, longed to return to the academic life. He joined Louis at the University of Waterloo, completing a master’s and PhD in philosophy. For years, he moved between the worlds of academe and law, alternately and sometimes concurrently, sitting on the tribunal and teaching at Fredericton’s St. Thomas University. He’s now back in Ottawa, mainly retired.

Most days he arrives in the early morning at a Bridgehead coffee shop near his home. Seated at a corner table before an open laptop, he edits his father’s journals from the Doig River years, hoping to publish them as a companion volume to his mother’s letters. He and his brothers often muse about writing a book together on academia, particularly about the small, primarily undergraduate institutions where they’ve spent their careers. “We all believe in the traditional liberal arts education,” says Paul. “I don’t think a narrow degree in science serves you in life the way a bachelor of arts does.”

But the future of these institutions seems clouded to them in the face of shrinking enrolments, tight government budgets and shifting student demand in favour of career-ready degrees. “In some ways, it’s a perfect storm,” says Leo. He has no doubt the schools will adapt and survive.

As our lunch draws to an end, talk turns to the pending holidays, and the best way to greet people in these diverse and secular times. Is Merry Christmas still acceptable? Or is it better to go with the more generic Happy Holidays? Inevitably, another debate erupts, with eye-rolling, finger-pointing and laughter.

No doubt John Groarke would have been proud.

I remember you all from St. Mary’s as smart and funny. Congratulations on your successes and your dad would be proud.

Great story. I love the idea for the book collaboration with the three of you.

Very interesting story. Your Mom must be so very proud. She has accomplished a great deal in her lifetime. So pleased to have met her and Mary.