For two years, curators at Galerie de l’UQAM, the art gallery at Université du Québec à Montréal, travelled the country, visiting studios, galleries and art fairs in search of artists who best represent contemporary painting in Canada. Out of 500 artists considered, 60 were eventually selected for its massive survey exhibition, The Painting Project.

The two-part show, which opened in May 2013, was by all accounts a huge success, attracting not just the usual gallery-goers, but collectors eager to discover young artistic talent. The Painting Project also brought in companies like RBC looking to acquire works for corporate collections. Galerie de l’UQAM director Louise Déry even made The Painting Project publicly available as an online exhibition and teaching tool through the Virtual Museum of Canada.

Like other university art gallery directors across the country, Ms. Déry is more than aware of the pressures, both internal and external, to build audiences – even if those visitors are sitting at their computers thousands of kilometres away. With administrative budgets getting tighter and funding bodies demanding more inclusive programming, the role of galleries as mere showcases for art collections is a thing of the past.

UQAM is lucky in that its location in downtown Montreal, surrounded by trendy restaurants and theatres, is highly visible, attracting passersby. But it is no longer enough for any gallery to simply hang art on the walls and hope people will show up. More than just a nice-to-have asset for faculty, staff, students and alumni, campus galleries are now reinventing themselves as vital cultural and research hubs, in tune with the needs of their local communities yet connected to the broader art world.

“It’s not possible anymore to focus on only one aspect of art,” says Ms. Déry. “Art is so much linked to everything surrounding us. It is linked to money, to intellectual development, to society, the place we occupy in the world. We have to network. We have to be linked to the market, to the intellectuals, to the art critics, the magazines, colleagues in the rest of the country and abroad. We have to make our productions known.”

University galleries and museums hold a unique place within Canada’s public art institutions. Academic freedom has allowed their directors and curators to become risk-takers who are responsive to both evolving social issues and artistic trends. But it wasn’t always this way. For the most part, university art galleries were originally established to manage and display institutional collections, ranging from paintings and prints to anthropological artefacts. Built through decades of donations and acquisitions, the often eclectic collections reflect the evolving mandates of the institutions themselves as well as the preferences of generations of curatorial staff and administrators.

At University of Toronto, the situation is more complex than most. Until recently, two distinct galleries with separate collections existed on its downtown campus, just 40 metres away from each other. The collection at Hart House was born in 1922 with the $200 purchase of A.Y. Jackson’s painting, Georgian Bay, November. In the following decades, the student centre acquired a substantial holding of Canadian paintings from the likes of the Group of Seven and Emily Carr. By the 1980s, it was clear that Hart House’s more than 600 works required professional care and so the university opened the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery in 1983.

The institution made a similar decision in 1996, when it launched the University of Toronto Art Centre in nearby University College to act as custodian to three major collections. During its early years, the centre focused on exhibiting these works, but after an expansion and upgrade in 2000, it began to show pieces on loan from external collections.

The proximity of the two galleries never seemed to be an issue, says Barbara Fischer, an associate professor in curatorial and visual studies at U of T and director of the Barnicke Gallery for more than a decade. But pressures mounted, particularly in terms of caring for the collections. After several years of planning, the two galleries relaunched in January as one entity with two separate gallery spaces known collectively as the Art Museum.

“As we developed, we found that we were collaborating more,” says Ms. Fischer, now executive director at the Art Museum. “Exhibitions were sometimes co-produced and we found ourselves increasingly wondering: are we fundamentally different? Do we need to be fundamentally different, or is there an opportunity here to do something bigger?”

One thing that hasn’t changed with the name is the focus on supporting students. The university’s fine arts, art history and museum studies programs look to the Art Museum for student research opportunities and curatorial experience, internships and work-study jobs. “There is this intensity of student life that is a part of every aspect of the Art Museum and that is very exciting and energizing. Some of our students are doing fantastic work there,” says Ms. Fischer. “Exhibitions that they’ve organized have travelled nationally, which is pretty much unheard of, I think, and have been getting awards. There’s a certain energy that comes with that; it’s just magical.”

At the Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s University – which boasts a broad and renowned collection, including three works by Rembrandt – working with students and faculty beyond the fine arts department has become a priority. “We reach out actively to students in health sciences, nursing, the hard sciences and the humanities,” says Jan Allen, the centre’s director and an adjunct professor of art and cultural studies. “Last year we worked with 51 different courses in the academic year with our collections or exhibitions, or our staff were doing custom seminars for courses. That’s very satisfying for us and is an area we continue to cultivate.”

While a curriculum-focused approach has successfully introduced new students to galleries at Queen’s and other institutions, convincing them to pop in for casual visits remains a challenge for directors. For students who may have never set foot in a gallery before, the experience can be intimidating. And galleries are competing with other extracurricular entertainment options. Ms. Déry at UQAM says it’s worth the effort, however, to capture the attention of young adults on campus before they move on with their personal and professional lives. “It’s a chance for us to help develop better viewers for art. This is the challenge.”

To that end, galleries are promoting themselves as welcoming and accessible spaces. At Queen’s, a visit to the Agnes Etherington is now part of incoming students’ orientation. Many galleries also invite groups to use gallery spaces for events, such as the student-run coffee houses that happen biweekly at Cape Breton University Art Gallery. The gallery at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax has previously collaborated with a Sufi spoken-word poet to host performances during Ramadan. Close by, the Dalhousie University Art Gallery has run a well-attended film series for years. U of T decided to federate and rename its galleries in part to make them more approachable. “The name ‘Art Museum’ was something that could be easily explained,” says Ms. Fischer.

Galleries are also doing outreach with local, national and international arts communities. Lending works to other institutions and touring exhibitions not only helps build long-time partnerships, but also helps offset costs. CBU’s art gallery – the only public gallery in the region – partners with local institutions such as the Centre for Cape Breton Craft and Design to bring in speakers. Saint Mary’s, along with galleries at Mount Saint Vincent University, Dalhousie, NSCAD University and two artist-run centres, developed a consortium called Halifax INK to produce catalogues and scholarly publications, which they presented at last year’s New York Art Book Fair.

A looming issue for all galleries is money. It’s a perennial challenge to find funds for much-needed upgrades to storage facilities or collection-management software. The University of Saskatchewan’s three galleries, which manage a collection initiated by the school’s first president in 1911, no longer have an acquisitions budget due to cutbacks.

All galleries receive financial support from their host universities for operational costs such as human resources, insurance and facilities management, and university advancement departments drive most gallery fundraising efforts. The Canada Council for the Arts and provincial governments offer vital funding for gallery programming, but even this support presents its issues, says University of Lethbridge Art Gallery director and curator Josephine Mills. “You get kind of stuck in this no man’s land, because the arts funding bodies will say that the university gets funded under postsecondary money. There’s this idea that universities are rich. … So, we’re often put into a different category than standalone public galleries.”

In recent years, as government agencies shift their demands so that all cultural institutions become more community-driven and offer interactive, inclusive programming, galleries have followed suit. CBU gallery curator Karie Liao says, “Our original mandate was collecting and displaying items from our collection, but now it’s providing things like childcare, or space for more diverse voices and local community members who aren’t professional artists.”

“Our public funders are really geared toward interactivity, participation and collaboration across the community,” says Ms. Allen at Queen’s. “These are guiding principles to ensure that people remain interested and that the collections and exhibitions have a real life in various communities, whether they’re on your doorstep or further afield.”

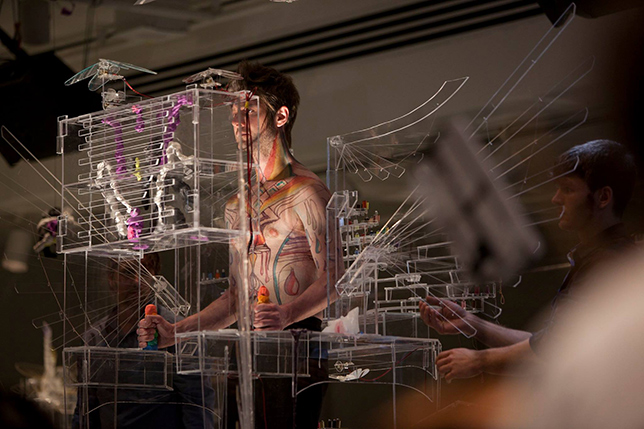

While directors maintain that their exhibitions are curatorially independent – not beholden to specific curricula or community needs – they have found inventive ways to connect with their peers at museums, non-profits and other groups through joint programming and one-off projects. When U of T co-hosted the Pan Am Games and Parapan Am Games last summer, the galleries took advantage of the events by producing a major exhibition focusing on body movement. “It brought together artists from all around the world,” says Ms. Fischer. “It gave viewers a chance to interact with the works that opened up different dimensions of the experience – sensations of hearing and listening and physical engagement.”

As part of a broader vision, the U of Lethbridge gallery engages in frequent off-campus programming, partnering with institutions such as the YWCA, public libraries and the Opokaa’sin Early Intervention Society. Dr. Mills is also an associate professor in U of Lethbridge’s department of art and part of a research team called Complex Social Change that looks at how to turn young people into active citizens, including through exhibitions that address activism and social issues. She is co-supervising a PhD student on an audience study which she hopes will turn Lethbridge into a leader in research on public engagement with art galleries.

“I grew up in Saskatchewan and you’re taught safety on ice on frozen ponds. So, you’d lie down flat if the ice is thin so you don’t fall through. If you stand up straight, through the ice you go,” says Dr. Mills. “University is the same thing: you need to have multiple points of contact. You need to have connections across the whole campus.”