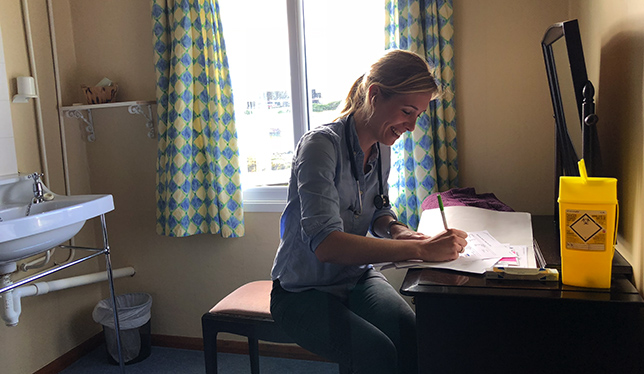

At first glance, the scene looks like something straight out of the 19th century, or perhaps a particularly realistic episode of Dr. Quinn Medicine Woman. In an idyllic, antiquated fishing lodge – wood paneling in the halls, photos of big fish on the walls – Katherine Soucie, a second-year medical resident at Queen’s University, is set up in a small room upstairs, modern medical equipment spilling out of her doctor’s bag and across the made-up double bed.

Downstairs, local villagers gather in an ersatz waiting room, climbing to the second floor to be examined – people getting flu shots, a woman with a cough that just won’t go away, a sheep shearer whose cut isn’t healing very quickly. For the latter, Dr. Soucie prescribes an antibiotic that will be sourced from the village’s medicine chest – a simple cardboard box that holds a cache of pills and ointments, held in trust by the local farm manager.

In the past, doctors often prescribed over the radio, and now they do so over the phone. The man fears that he may need to be referred to the main hospital, across the channel, in the capital. “Stanley may as well be Toronto, as far as they’re concerned,” Dr. Soucie tells me afterward, with a tentative smile. “These are farmers, and there’s a lot of work to be done.”

I’m on the Falkland Islands, a British Overseas Territory in the extreme South Atlantic that, by reasons both geographic and political, remains one of the most remote inhabited places on earth. Isolated from Argentina, their closest mainland neighbour with whom they fought a war in 1982, this archipelago is largely self-sustaining, the 2,500 hardy residents depending somewhat on supplies and transportation provided by Royal Air Force-operated Airbridge flights to England, 18 long hours away. For the last three years, the department of family medicine at Queen’s has operated a residency program here, sending newly minted doctors with an interest in rural and remote medicine to learn their trade and practice in this far-flung corner of the earth.

The program got started with a casual conversation – a member of the Falklands’ tiny legislative assembly was attending an international meeting related to the Commonwealth Games and happened to mention to a Canadian colleague the island’s challenges with remote medicine. The colleague, a Queen’s alum, in turn passed word on to Geoff Hodgetts, director of medical education in the department of family medicine at Queen’s. After a Skype call and an in-person meeting at the British High Commission in Ottawa, Dr. Hodgetts visited the Falklands in February 2015, laying the groundwork for the residency.

“I got a lot of tilted heads, people asking ‘Why there?’” Dr. Hodgetts remembers, noting that some people couldn’t even point to these islands on a world map. “I collect stamps, so I knew exactly where they’re located.”

Since signing a medical training agreement, a total of 17 Queen’s residents have served here, one at a time, in two-month blocks. In addition, the department is expanding the program with a third-year, postgraduate enhanced training scholarship sponsored by the Falkland Islands government, with a one-year return of service requirement. Belle Song, the first recipient, completed a residency here last year.

While residents regularly travel out to the outer islands and hinterlands to see patients, much of their time is spent at the King Edward VII Hospital in Stanley. There, I join Dr. Hodgetts, along with Michael Green, head of the Queen’s department of family medicine, and Brent Wolfrom, the incoming program director with overall responsibility for the postgraduate family medicine program, my trip here coinciding with their weeklong site visit. Beccy Edwards, the Falklands’ indefatigable chief medical officer, leads a tour of the maze-like space, which includes wards, emergency room, labs, dental facilities, surgery theatre, X-ray suite and a labyrinth of waiting rooms, staff offices and other facilities all under one sprawling roof.

We pass local characters in the hallway, including a smiling, moustachioed man, who Dr. Edwards tells us sails National Geographic film crews to Antarctica on his yacht (“He’s as eccentric as they come!”). She shows us the X-ray suite where, until recently, Dr. Edwards says, they also created images for the local veterinarian, telling a funny story about a runaway cat. We stop at an isolation unit, most often used to house international fishermen from offshore squid boats who sometimes arrive with serious cases of tuberculosis. Our tour finishes in the emergency room, where we find Dr. Soucie, who happens to be treating Dr. Edwards’ own mother, recovering from a bruising fall.

In addition to the obvious benefit of an extra set of highly trained hands, Dr. Edwards says the Canadian residents bring their own perspectives. “They have fresh faces and new ideas, and they’re at the peak of their knowledge point,” she says. “It’s wonderful to have these young, energetic doctors.”

And the Canadian medical residents, who live across the road in Canada House, a home purchased and renovated to billet them, enjoy a number of advantages, too. Bumping out in a Land Rover to a remote corner of the territory, a place called Volunteer Point, in search of penguins, I chat with Dr. Soucie and Sandra Huynh, newly arrived just that day, who will be taking Dr. Soucie’s place.

Both plan to practice in small-town settings, and Dr. Soucie, at the very end of her two months here, notes that she’s gained skills that will serve her well in that pursuit. Because severe cases need to be medically evacuated to either Chile or Uruguay, doctors here have to learn to stabilize patients for longer-than-average periods of time, and she’s had hands-on experience with that on various occasions. She adds that she’s also seen a wide variety of conditions, beyond what she might see back home, from those sickened fishermen to a serious trauma situation where a couple, camping near the sea, took shelter in a shipping container and were subsequently blown hundreds of feet by hurricane-force winds.

“There’s just one hospital here,” Dr. Soucie says. “And when they walk through the door, you need to help them, right then and right there.”