Despite closures, travel restrictions and reduced ancillary services spurred by COVID-19, Canadian universities saw record-high surplus revenues of $7.3 billion in 2020-21. According to a recent report from Statistics Canada, that’s the largest windfall since the agency started collecting such data two decades ago.

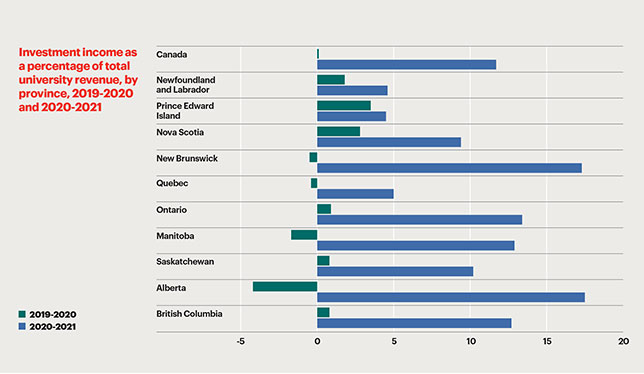

Provincial funding and tuition fees remained the top two sources of revenue. But the strong financial performance was attributed primarily to $5.4 billion in investment income, the report indicated. “This is something we’ve never seen historically,” said André Lebel, chief/program manager for the agency’s Canadian Centre for Education Statistics, noting that the surplus coincided with a red-hot stock market. By comparison, universities earned just $44.3 million in investment income in 2019-20, and brought in a total of $1.4 billion in annual revenue, on average, over the previous five years. With the stock market starting to cool early in 2022, the report notes that similar investment returns are unlikely for the current fiscal year.

The report’s findings also do not point to a simple cash windfall, Mr. Lebel said. Investment revenues are often restricted to predefined purposes. And aside from the record investment income, Mr. Lebel said “there was no big surprise.” The report showed that provincial funding continued to decline overall, with five provinces experiencing a decrease and five an increase. Universities also continued to rely heavily on tuition fee revenue – particularly from international students – to make up for shortfalls in provincial funding.

Bust and boom

This year’s record revenues are in stark contrast to projections just one year ago. In fall 2021, Statistics Canada predicted that universities across the country could have lost between $438 million and $2.5 billion of projected revenues for 2020-21. Mr. Lebel said that analysis was intended to assess the potential financial impact of a drop in enrolment. It was based partly on study-permit data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) that has historically correlated with international student numbers. “What happened, which had never happened before, was you had some international students studying from abroad first, and they didn’t have a student permit because [IRCC agents] were not able to produce them fast enough,” said Mr. Lebel.

While Statistics Canada data on student enrolment for 2020-21 won’t be released until November, the agency’s report on university finances showed that tuition revenue increased in 2020-21 by 2.7 per cent from the previous year (although at a slower pace than over the past five years).

Riaz Nandan, national treasurer for the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS), said that increases in tuition fees are being felt by students more than ever. “Students have been complaining for years but, this year especially, the cost of everything is just going up,” said Mr. Nandan. As a result, the federation would like to see the revenue windfall “directed to the things that students have been calling for, for a long time – essential services like food banks, mental health support, academic and advocacy centres, student housing, health care – big things that go towards their basic needs. This is a chance for the universities to catch up on that.”

David Robinson, executive director of the Canadian Association of University Teachers, said the fact that student enrolment numbers seemed to hold up was a positive takeaway. But there were also signs of vulnerability. “Despite the overall report of a very large collective surplus, there’s a pretty fragile foundation underlying it that universities are going to have to deal with,” he said. “We saw a bit of an anomaly in terms of interest income that made a major contribution to the overall surplus. But when you look at the underlying fundamentals – government funding, tuition-fee revenues, all those things,” he said, “I worry that the fundamentals going forward aren’t great.”

Cutting costs

Universities didn’t just break one record in 2020-21. The report found that they scaled down expenditures by 3.8 per cent from the previous year, which is the sharpest drop in 20 years. Salaries and benefits, the largest expenditure category, decreased by 0.8 per cent. However, that decrease wasn’t shared equally. Non-instructional staff salaries fell 1.6 per cent, academic staff salaries by 0.2 per cent.

Mr. Lebel, who is also the lead on Statistics Canada’s University and College Academic Staff System (UCASS) survey, said the agency’s data shows that the number of full-time academics and their salaries both increased in 2020-21. That suggests universities employed fewer parttime academic staff, he said.

CAUT’s data also points to cuts in contract academic staff, Mr. Robinson said, although those numbers aren’t conclusive. “The problem is UCASS doesn’t collect data on part-time or contract academic staff, so we have no idea exactly how many there are or what their long-term progression is,” he said. “I would hope that one of the things that we’d want to take a look at from a policymaking perspective is getting better data on how many contract academic staff there are, and what the trends are over time.”

Eighty-five collective agreements involving CAUT member associations are set to expire between now and the end of next summer. The record surplus revenue will “absolutely” be a factor in those negotiations, Mr. Robinson said. “People are going to look at the fact that universities and colleges have weathered the COVID storm relatively well,” he said. High inflation will also factor in, he added. “Salaries haven’t really matched that increase over the years, so people are looking at real declines in terms of their salaries and compensation. I think there’s going to be a lot of pressure at the table, and it could be a very long, cold winter.”

What’s new? The financial windfall detailed is just one more instance of universities making money off the inadequately protected — students, sessional instructors and other underpaid and overworked employees and now, a big helping of students from abroad desperate enough for Canadian university certification to pay outrageous tuition. Again, not too much new here at our university factories who have from their historical beginnings served as “personnel offices,” supplying our engines of commerce and industry with an obedient and even on occasion well-trained workforce. To borrow from the late Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., “and so it goes.”

This is unbelievably poor reporting about the financial position of universities. It confuses revenue with net income/surplus (there is no such word as surplus revenue in the accounting world). It fails to distinguish investment portfolio revenue from operating income.

The single most important measure of how a university will fare is the state of its operating accounts and direct ancillary operations (food services, residences etc.). While there was a surplus (revenue minus expenditures) in many universities operating accounts in the year ending 2022, it is nothing like is reported in this article.

By focusing on the wrong measures, wrong conclusions can be drawn. You can do much better than this in your reporting.