Anxiety, academic difficulties related to online learning, concentration problems and pandemic fatigue have been named in a national report as leading reasons why students have been seeking help for their mental health and wellness on campus.

Titled Campus Mental Health Across Canada: The Ongoing Impact of COVID-19, the report, published by the Mental Health Commission of Canada and the Canadian Association of College and University Student Services (CACUSS), is based on responses to an online survey received from student affairs and mental health professionals at 69 Canadian postsecondary campuses. Three-quarters of them were universities. The survey, conducted in mid-2021, covers the 2020-2021 academic year and the pandemic’s second and third waves. It follows similar surveys done each year since 2018.

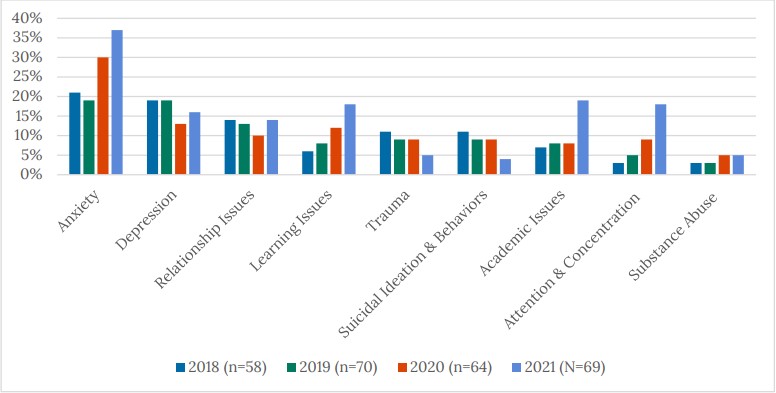

The responses reflect the most prevalent concerns students have sought help for, as ranked by the respondents. Anxiety has remained the leading – and a rising – reason why students have come for help over the years, with a 29 per cent rise in its ranking as a leading concern since 2018. Depression, the second leading reason, dropped slightly in its prevalence over the four years, although it is starting to rise again.

For students, having the pandemic’s uncertainty hanging over them, as well as the absence of activities that support well-being, such as going to the gym or connecting in person with friends, “was a really tough environment,” said Lina Di Genova, director of strategy, assessment, and evaluation for McGill University’s student services. She co-authored the report with Tayyab Rashid, a clinical psychologist at the University of Toronto Scarborough.

“If you don’t know what’s coming, it increases everyone’s anxiety because you don’t know how to plan, you don’t know how to prepare,” said Dr. Di Genova. “For students, the biggest impact is on their learning.”

Attention and concentration issues have seen some of the fastest growth, increasing by 16 per cent a year. There was a significant spike between 2020, when they were at nine per cent, to 2021 when they shot up to 18 per cent. Similar growth was seen in academic problems, such as trouble accessing virtual technology and communicating with faculty.

professionals/student affairs leaders.

A new mental health problem

Respondents also reported high levels of pandemic fatigue among students by summer 2021. (“Pandemic fatigue” was defined as being so tired of public health restrictions that students are unable to do what is essential for their well-being.) The researchers found that pandemic fatigue was significantly associated with anxiety, isolation, financial worries and a heavier academic workload as a result of the switch to online learning.

Since there is no specific treatment for pandemic fatigue, Dr. Rashid suggested that universities look at reducing its associated factors: “Maybe it’s easier to have programs for 2022 that will decrease social isolation for students,” he said.

Calling the report’s findings “very consistent” with its student body, the University of Waterloo’s counselling services leadership team said that weekly virtual class discussion boards were a particular source of online learning fatigue for students. Professors set these discussions up to help students stay engaged with each other during in person restrictions. However, when used with every course, “students experienced it as added academic demand and pressure to be constantly logged in online,” the team wrote in an email to University Affairs.

Keeping support services online and available despite other service disruptions was important to their students, the team added. Its online group counselling was especially appreciated because it helped students feel less isolated.

More than half of student-service leaders reported difficulties in navigating legal and other limits to providing ongoing mental health support to students living outside of the jurisdiction where their professionals are licensed to practise, including students in other provinces or countries. Many universities turned to third-party vendors such as My Student Support, a counselling service app operated by the Toronto-based human resources company Lifeworks, to provide live help and other resources that did not contravene jurisdictional rules.

When providing service virtually, “the first thing I ask during COVID [is], ‘Johnny/Amalie, where are you?’” said Dr. Rashid. “Because what if something happens during the session or after the session and we know that they are in Beijing? How can we provide them services, especially if, God forbid, they’re suicidal or are having some sort of a crisis?” The report provides recommendations for student services personnel, such as assessing levels of distress early in the school year to identify high-risk students, and involving students in the design of campaigns to reduce pandemic fatigue. It also has a lengthy appendix with ideas for building and delivering services based on clinical practice and related research literature.

Looking ahead

Both researchers stressed the need for student services to recognize that students may go through yet another transition this fall as campuses attempt to offer more in-person learning, activities, and services, including through hybrid models. Dr. Rashid said that one of his clients expressed anxiety in anticipation of having to master yet another new routine and set of study skills after doing the first two years of their degree remotely.

“People have been through so much change that I think we’re still going to need a little bit more time to settle in,” added Dr. Di Genova. “That’s something to pay attention to and not just assume it’s going to be business as usual.”

Keeping the student service infrastructure flexible and adaptable will be key, both researchers said. The Mental Health Commission of Canada’s national standard for postsecondary student mental health is one tool that service providers can use to not only assess campus services but also determine what would be best provided externally, possibly through partnership.

“We do see much more effectiveness and impact when we are agile, flexible, focusing on early access and early intervention,” agreed Vera Romano, director of McGill’s student wellness hub. The hub had only been created through an integrated service model six months before the pandemic struck. Dr. Romano called it “an excellent fit” for the pandemic’s demands, including moving services online. But she added that McGill’s delivery of services has also been helped by continuously evaluating what’s working and what’s needed, by consulting with data, including the campus mental health report, as well as with staff, faculty and students.